Stop! Homer Time

12/6/19 - We rave about the power and politics of translation inspired by Emily Wilson's mind-blowingly less-misogynist translation of the Odyssey into English. And we talk with translator Katrina Dodson.

Transcript below.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | Spotify.

CREDITS

Producer: Gina Delvac

Hosts: Aminatou Sow & Ann Friedman

Theme song: Call Your Girlfriend by Robyn

Composer: Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs.

Associate Producer: Jordan Bailey

Visual Creative Director: Kenesha Sneed

Merch Director: Caroline Knowles

Editorial Assistant: Laura Bertocci

Design Assistant: Brijae Morris

Ad sales: Midroll

TRANSCRIPT: STOP! HOMER TIME

[Ads]

(0:34)

Aminatou: Welcome to Call Your Girlfriend.

Ann: A podcast for long-distance besties everywhere.

Aminatou: I'm Aminatou Sow.

Ann: And I'm Ann Friedman.

Aminatou: Bonjour Ann Friedman.

Ann: Hola.

Aminatou: [Laughs] I need you to give me one more sentence than hola. Also I love that I say this -- my accent is this. Give me one more sentence than that.

Ann: One more sentence than hola? What? I don't . . .

Aminatou: Yes. I want you to go further in your greeting to me.

Ann: Como estas?

Aminatou: Thank you. [Laughs]

Ann: Wow, and now you are the one trolling me with a thank you response.

Aminatou: Yes! Gracias. You know, I just want to push the boundaries of us using our foreign languages on this podcast.

Ann: Bienvenidos a Call Your Girlfriend. [Laughter]

Aminatou: Thanks for speaking Spanish with me because we just missed Women in Translation month.

Ann: I mean this is so classic us where we're like what a great idea, we are so excited to talk about literary translations of women's work, translation done by women. You know we are big book nerds. And then lo and behold the whole month goes by and we've missed that what is actually Women in Translation month. But you know what? Still a worthy topic and we are still going to talk about it.

[Theme Song]

(2:12)

Aminatou: Here's my problem with all these XYZ months. If we gave people the credit that they deserved we would not be having to silo people, like celebrating people in specific moments of the year. So Aminatou rant out but it makes me annoyed that we have months for things that are cool and important.

Ann: I hear you. I mean so in this particular case it is not something that has long been on the Hallmark catalog, Women in Translation month.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Ann: No, I mean it was started as an activist thing. In 2014 a book blogger named Meytal Radzinski was like "Listen, a tiny fraction of the US book market, we're talking less than 3%, is literary translation. And of that tiny slice an even smaller percentage of those translated works are the work of women writers in translation." So like less than 30% of 3%. I don't know the full math on the fractional number of translated works by women. But frankly if you are buying books in the United States and you are buying books in English and reading books in English you are missing literally everything written by women in any other language. That's kind of what that number means. And I think that's why it's like oh, here's a month to be like you know, if you are a huge nerd who pays attention to such things like yours truly it's maybe a good month to read a work in translation, either a work by a woman or a work translated by a woman.

Aminatou: Whew, I'm processing all of that information.

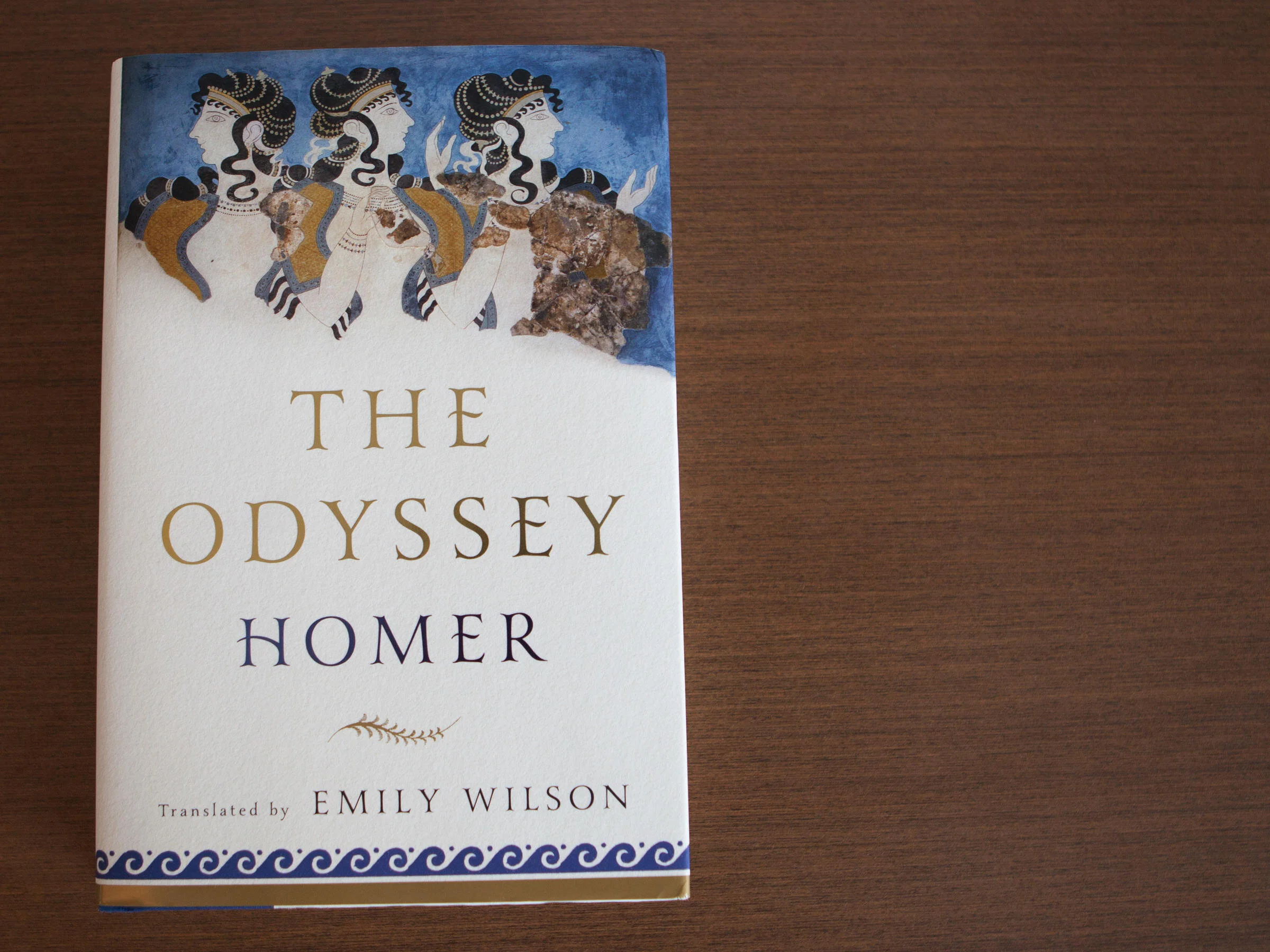

Ann: Well okay. And actually more specifically before I even knew it was Women in Translation month I was honestly having an intellectual meltdown in the best way possible because I picked up this translation of The Odyssey by Emily Wilson. I mean by Homer but translated by Emily Wilson.

(4:00)

Aminatou: [Laughs] No. I think it's okay to say that this version is by Emily Wilson.

Ann: Totally. Okay, inspired by Homer, written by Emily Wilson.

Aminatou: Home could never Ann. He could never.

Ann: Homer wishes right? Anyway and I -- it has been blowing my mind on so many levels. It is like all I want to talk to people about. And I received it as a gift. I've recently given it as a gift which to me I'm like that's how you know this is important to me. And when I mentioned it to you you were like oh my god, how did we not talk about this a year ago when I was obsessed with it? So can we just geek out about this translation of The Odyssey for a minute?

Aminatou: Oh man. The number of times that I had to read The Odyssey in French school or had to write about it or whatever, and like I get it, hero's journey. You know what I mean?

Ann: Whomp, whomp, wank emotion.

Aminatou: Right, like whomp, whomp, the canon.

Ann: Yep.

Aminatou: But you know, also I'm like if your journal can survive millennia I guess we've got to give it some respect, you know what I'm saying? I hope someone finds all my text messages one day and it's like The Odyssey in 17,000 whatever. But anyway it also just represents a lot of other firsts right? It's like okay, first woman translator of The Odyssey. That is a huge deal and it's also something that I don't think until I read it I had fully actually metabolized, you know? It's just the realization of like oh yeah, I live in a world that is shaped by men including the translated works that I read. That was an actual like . . . I had not like fully thought that through. And so I think that waiting for that to sink in, that seems pretty monumental to me. It's also like the first English translation that has the exact same number of lines as the original. It's the first that's in regular meter. It's radical.

Ann: It is.

(5:55)

Aminatou: And it's radical from the opening line. So it's just this thing that -- you know, I'm like oh, is this what happens when people who don't usually have access to a specific kind of area get access? Like shit gets blown up? I love this. Like this energy all the time.

Ann: I also love that the first maybe quarter of this book is an introduction and a translator's note in which she describes her process and essentially why this work in translation is really different than other translations of The Odyssey, why she felt it was necessary. I mean it really is the kind of conversation that I don't really remember having in college and high school classrooms but seems like the modern -- like the kind of adult version of that conversation which I crave which is to say she really kind of breaks down why is this work important in history? But also what has been missed because it is venerated as important?

And so your point about like oh wow, the layers of it being filtered through men's experiences, for example she's like "Listen, the oldest English translations of The Odyssey are no closer to ancient Greek than our modern English is." Right? Like it really is not . . . those were fully like, you know, one guy's interpretation brought into what was then modern parlance to tell the story. And subsequent translations have really tried to hue towards early English translations. And her radical thing is like guess what? I'm just going to hue to the Ancient Greek and the modern. I'm going to say truly translating this story not only into English but for this moment requires me to actually not take into consideration other works by men. Right? It's just me and Homer. It's just like me and the modern English language.

And she does preserve certain things like as you said the number of lines. But I love this idea of her just being like you know what? There is a whole construct around the way this work is translated and we don't really need that. That's not serving the reader.

(8:00)

And I'll give you an example. She mentions that a lot of the characters in other translations are described in very repetitive ways. So it's always Wise Athena or something like that which was designed in an oral tradition to allow listeners to really like oh, I'm going to sit up and take notice. This is Athena we're talking about here, the wise one. Whereas when you're reading it in print people who are reading this translation of The Odyssey are literate, are probably very comfortable consuming the written word, and they don't need repetitive descriptors to recognize Athena and who she is. And therefore she can be a little bit more free. She can use other descriptions of who Athena is. Like she's really not only thinking about how this work will be received in the modern context but she's like you know what? I'm taking an oral tradition and translating it into a written tradition, so other types of translation. And that's where my mind fireworks are just going, right? I was like loving it.

Aminatou: Man, thank you for nerding out with me on this. [Laughs] So . . .

Ann: The real tagline of this podcast, thank you for nerding out with me on this. [Laughs]

Aminatou: I know. So here's the thing, something that I want to go back to something that you said a little bit earlier about how part of the decision that she makes is she contextualizes The Odyssey in modern times, right? And so -- and basically within the current political climate that we're in. And so that is a very deliberate choice right? She makes a choice to really embrace this modern tradition of like white man anti-hero like your Walter Whites or whatever. And there's a part of that that is like okay, great. Like some would say it's kind of an activist stance. I don't agree. I think that is an intellectual stance. But the thing that I love about it is that it doesn't mean because she has these politics or she prioritizes that that she's also not being accurate.

Ann: Of course.

(9:50)

Aminatou: And it's just something I've been thinking about a lot. She really points a lot of the misogyny in the text right? And the misogyny in previous translations. And so there's this moment where basically Telemachus murders all of the -- you know, he murders all of the slaves who slept with Penelope's suitors. And every other translation of the young women had always been super -- it had always been misogynist slurs. It was like they're whores, they're creatures, slutty, all of this stuff. And everybody's always been very agreed that that's just like -- it's like well, you know, the Homer time, that was very sexist. Like this is what's happening.

Ann: Stop! Homer time. [Laughs]

Aminatou: You know, Homer time! And she's just like no, slut shaming is . . . she's like slut shaming is something that newer people have brought to this text. And so to me I'm like wow, this -- I'm like are you saying that there's anachronistic misogyny in translating this work? [Laughs] And so like I just keep being stuck on the . . . you know, it's like we talk a lot about diversity and inclusion like they're supposed to be some sort of moral imperative. And sure, like that's fine, like the world should be reflective of how people are or whatever. But I'm also like it makes creative sense and it makes business sense. Like in this case I was like wow, it took a woman to fix a thing that was not true.

Ann: Well that is 100% true and I think one reason why I am so engaged in the conversation around this book in particular is because it is baked into all kinds of other culture we consume because this story is perceived as so canonical and so foundational. And I had actually forgotten when I picked up this book recently that I had really come into contact with her work as a critical translator last year when she was tweeting about the sirens and how they appear in this book. Which is, you know, maybe you picture them as three sexy mermaids on a rock tempting sailors. I think that's kind of how I would summarize who are the sirens.

(12:00)

Aminatou: Yeah, right. It's like sexy babes.

Ann: Sexy babes on rocks. And this crops up in all kinds of retellings of The Odyssey, like these characters are there again and again. But here is what she tweeted. She said "But the Homeric sirens passage in book 12 is surprising in at least two ways. One is how short it is. This episode has become a much bigger part of The Odyssey in modern retellings than it is in the Homeric poem." Which interesting, right? Like you have taken a thing that is gazing at sexy, seductive women and made it a bigger part of this story than it truly is. So there's that.

Secondly she tweets "The sirens in Homer aren't sexy. For example we learn nothing about their hair in contrast to other divine temptresses. The seduction they offer is cognitive. They claim to know everything about the war in Troy and everything on Earth. They tell the names of pain." And so really they are seductive to our hero who wants to understand the world, which who doesn't right? But they are not seductive in the like these are some sexy babes sense, right? And even that is one of those things where if you ever needed a case for why do we need a diversity of people translating stories that have wormed their way into every aspect of the western literary canon, like there you go. That is the perfect anecdote to summarize the reality check. And also it's so much more interesting to be seduced by knowledge, don't you think?

Aminatou: I mean, Ann, you are melting my panties off. Thank you. [Laughter]

Ann: Wow.

Aminatou: Excuse me. You know, but it's also this kind of thing where it's so easy to frame this conversation around like oh yeah, this is what the female perspective brings to translation.

Ann: [Laughs] I love your bro voice. Would you please say that again in your bro voice?

(13:55)

Aminatou: [Laughs] You know what I'm talking about.

Ann: I do.

Aminatou: But it's this thing where I was like is anybody running around asking male translators how their male perspective has really hampered their work?

Ann: Yes!

Aminatou: Because this is -- it's just like what? What is happening? And this is why I love learning. This is why I love learning. I love reading books and I love learning. You know, something that you think you're familiar with and something that is so . . . you would not catch me just reading The Odyssey for no reason at my big age and it turns out there is still something to learn here. And I don't know, I just am very grateful for Emily Wilson and for all the women who do this very intense and very vital kind of work because wow, like if Homer is not being translated right what else are we missing out on?

Ann: Absolutely.

Aminatou: Ugh, this is all churning up a lot of what I think about a lot of things. Let's take a break. [Laughter]

[Ads]

(17:40)

Ann: You know, I go back to this idea of Women in Translation month because on one level I think I thought a lot about how in works that are well-regarded, works that are seen as foundational like The Odyssey, I think about who's missing from that right? Which authors -- which creators -- are missing from what is perceived as canonical. I think about that a lot. I think a lot less about interpretation of that work and also how that is a loss that we experience as people who are interested in the world when only a certain demographic is critically interpreting that as well. And I think that layer is what I'm really getting out of this translation. I mean I love . . . this is like full-on nerd raving now but I love work that makes me consider the kind of everyday things I'm consuming even when it's not the work itself. So when The Odyssey is closed and sitting by my bedside table I am still thinking about now, because it's forefront of my mind, how things around me are translated right? Who is picking this item and packaging it for Trader Joe's and what was its original form? You know, just every mundane choice about who gets to be a translator of culture and of art in the deepest sense, the broadest sense.

Aminatou: Right. I mean it is such a gift that we have as humans that there are so many ways to understand each other and to have access to each other's ideas and words and brains. And translators are a vital part of that and it's just so . . . I don't know, it's just been making me think . . . it's making me think a lot about who are the middle men in the transaction of understanding other human beings? And it also just makes me think a lot for myself about, you know, how my thoughts are organized in French versus how they're organized in English. And even in the process of writing our book what kind of writer I am in English because I think that that's the thing I've been trying to understand about myself for a long time and it is now coming into focus for me a little bit. And language is so mysterious and it's so, so, so, so important. The work of translation, it's not just . . . the work of translation is not transcription, you know?

(20:00)

Ann: Right.

Aminatou: And so I think that a lot of people just don't understand that. Translator works are not line-by-line translations or just, okay, I'm going to faithfully hue to the words that are here. You are translating a mood. You're translating emotions. You are translating a culture. And all of that is -- I'm like that's art. That is art and, you know, I'm fluent in languages that I do not have the skill to translate works in. That is a true labor of intellect and art so I'm very . . . I admire that a lot.

Ann: 100%. I love what you said about how there's never a one-to-one because of the mysteries of language right? There is no such thing as a translated work that is not an interpretation.

Aminatou: Right, and it's a very intimate process. I'm thinking about -- I will link to this in the show notes -- this piece that Teju Cole wrote in The New York Review of Books that is essentially about translation. And it just . . . it's a really lovely sentiment because he talks about his books being translated into other languages and I can't even imagine the relationship that you have to have with someone who literally will take your words and convey them in another language. And also just he contextualized it so much into the work of other literary translations. But it was just a really lovely piece that I will link to in the show notes. I don't know Ann, this is bringing up a lot of feelings for me. I love it.

Ann: A lot of feelings as a consumer of art? A lot of multilingual feelings?

(21:45)

Aminatou: A lot of feelings of what do I think I know that I don't know/

Ann: Whoa, yes. [Laughs]

Aminatou: You know? And I feel like that's like actually the . . . I don't know, so much of adult life has been this for me. Every day I realize that a thing I've been told to believe is actually not how it is. And that's a little bit rattling.

Ann: Completely. I mean in some ways I think that the process of growing up is continually recognizing how little the things you think you know are true in any objective sense.

Aminatou: Hah, always be learning. Always be learning.

Ann: Hmm, I'm trying to find this quote. It was a book review, I think it was in the New York Times Book Review several months ago, and it was a line embedded in a review of something. It wasn't like the subject of an essay. But I'm paraphrasing the quote which goes something like all writing is work in translation. Like you are taking things that are not experienced verbally and certainly not in the written word, experiences in the world and emotions, and like dynamics, and putting a name to them. And that process is extremely imprecise right? That is a translation as well. That's something -- I thought about that quote which I'm so sorry I do not have at hand to credit the writer -- but I thought about that quote a lot as we go through our own book writing process. And there have been so many times when we're like how do we even begin to capture this thing that, you know, has happened between us or that one or both of us have felt, that there is just not a commonly accepted language for?

Aminatou: Ugh, oh my gosh. Yeah, that's so real. It's like speaking of that Teju Cole piece I was telling you about one of the things that Teju Cole talks about with his translator -- I'm just going to go ahead and read it to you because I feel like it is still blowing my mind -- so he's basically talking about the translator who has translated already four of his books into Italian right? And so he says "Recently she was translating an essay of mine on the blackness of the panther which ranged on various matters from race, the color black, and colonialism, to panthers, the history of zoos, and Rainer Maria Rilke. It wasn't an easy text to translate. In particular the word blackness in my title was a challenge. To translate that word she had considered . . ." Uh, I'm not going to say these words in Italian because I don't know how to say them, "both of which suggested negritude. But neither quite evoked the layered effect that blackness had in my original essay. She needed a word that was about race but also about the color black. The word that she was looking for couldn't be the word for darkness in Italian which went too far in the optical direction omitting racial connotations. So she invented a word, thus the title." And then the title of the essay totally changed. And I was like this is hard work people.

(24:52)

Ann: Yeah, I mean I . . .

Aminatou: You know, it's like the language of Ferrante and Dante. You've got to innovate still.

Ann: Ferrante and Dante! [Laughs]

Aminatou: Listen, that's from the Teju Cole piece so . . . [Laughs]

Ann: I love it, yeah. No I love it. And it reminds me of actually another thing from this Emily Wilson intro to The Odyssey that I've been thinking about in terms of how words that actually don't have a one-to-one translation or meaning get interpreted as having that. So she talks about this term xenia which is the root of xenophobia. And if you asked me, before reading this translation without access to a dictionary, I would've said that means fear of strangers or a dislike of strangers.

Aminatou: Mm-mmm.

(25:45)

Ann: Well she sort of says -- she goes in deep to sort of say xenia really means guest friendship, like it's a hyphenated term.

Aminatou: Yep.

Ann: Which has to do with the welcoming of a stranger who you kind of perceived to possibly be a peer, i.e. someone with the financial resources to travel, who is not enslaved, who you are kind of obligated by like, you know . . .

Aminatou: Hospitality baby.

Ann: Exactly. And it's like a slightly more complicated version of the kind of Christian welcome the stranger vibe. But there's something about the hyphenated guest friendship that I thought was really interesting, and the fact that it is not just about the category of being stranger or friend or stranger or kin; it's about this category of being a stranger who has every right to expect a warm reception. It's sort of like there's this idea of . . . there's a value embedded in that right? Like the term itself implies it is of value to welcome a stranger on your doorstep. It's altered how I think about the term xenophobia.

[Music]

[Interview Starts]

(27:25)

Katrina: I think that translation, it's both a very mysterious process for people because people don't often think about it even being necessary but at the same time it's very intuitive.

Gina: Translator Katrina Dodson.

Katrina: We all translate to some extent. Someone once asked me "Well when did people start translating? How did it all begin?" I said well ever since there's been language we all have a different way of saying things. Literary translation, you have . . . you're trying to balance the semantic content or the meaning of what's being said with all the other information that language brings with it. So kind of tone of voice, connotation, register, all these things that go beyond the dictionary. So when I translate I think a lot about voice. I try to get inside the voice of the writer, you know, certain attitudes or the rhythm or how I feel when I'm reading them and I try to figure out how I can recreate that in English.

Ann: Something about translation feels political in a way I guess which is to say . . . I mean it's funny, I thought a lot about over the years who am I reading? What writers' voices am I consuming? Am I only reading work by straight white men and women? Am I reading -- you know, all these questions. And I think that really trying to put an active priority on reading work and translation is something that I came to surprisingly late given my politics about other types of reading. And I'm curious your thoughts about that and about some of the dismal statistics that we've seen about how much work actually is translated into English that does make it into the American market. Do you have thoughts or feelings about that?

Katrina: A lot. [Laughter] I'm really glad to hear you say all of that and even just the fact that you're putting this focus on the show shows that, you know, it's a great vote of confidence in that translation is something important to think about. And I think what's happening in the publishing world and translation world is something that's happening in the culture at large in that we're talking more and more about representation. You know, the importance of hearing from a lot of different voices that have been suppressed systematically in the past. And a lot more of these small independent publishers and even translators are thinking about well, why have I been translating a whole bunch of white men without thinking about it? And let's think about can we translate more white women? Can we translate more books by people of color?

(30:18)

Because I think a lot about why or how gender or identity matters when you translates, and obviously you can't always share the gender and identity of the person you're translating. But I think definitely translating Clarice Lispector as a woman I felt that I was much more attuned to just certain nuances of language or just, you know, you just feel . . . different words hit you differently.

So for example my biggest fight that I had with my editor over a translation, you know, a matter of interpretation, was over the word escritora. And escritora means writer but it's gendered female and he wanted it to be woman writer. [Laughs] I was like it's just writer.

Ann: Right.

Katrina: He said woman writer, that's just the translation. It's black and white. That's just how it is. And I was like wrong side of history. In this moment you get the gender eventually. So we -- in English you find out that it's a she but my point that I made against woman writer just being the black-and-white translation of that term is when you put a gender tag on a word in English you're making a point about gender. So you don't say the female president of Brazil met with the female president of Germany. You know, you don't say my cousin the female doctor. You just say doctor. You say president. But if you want to talk about say the first female president of the United States then you're talking about that in terms of gender.

(23:05)

So I think there were things like that where, you know, being a woman and knowing how much weight there is on a term like woman writer, which is neither feminist nor misogynist but it's definitely politically charged when you say woman writer, you're talking about the case of women writers. You're not just talking about a writer writing in her notebook. And so I said Lispector, she was a feminist but she wasn't -- she's not making a point about gender here; she's just talking about a woman. So it's things like that where I think as a translator you're making these choices in every sentence, in every paragraph, on every page and your interpretation matters a lot.

Ann: Right. I love that. After I made my commitment to read more literature and translation I'm really lucky because my local independent bookstore -- shout-out to Skylight Books in Los Angeles, California.

Katrina: Oh I love them. Hey Skylight! [Laughs]

Ann: They have a great shelf of literature newly in translation or things they are sort of paying attention to. And like, you know, love the curation of an independent bookstore but I really appreciate that there is a little bit of a go-to place for me to act on this desire to read more work in translation. And I'm curious if you have advice for people who are not so lucky as to have this shelf curated by their favorite indie bookstore, how they might go about diversifying the sort of language of origin when it comes to the books that they're reading?

(33:45)

Katrina: Yeah. I would also emphasize that independent bookstores are really great. I'm here in Brooklyn, I'm at the Center for Fiction. They actually are letting me use their podcast room, thank you.

Ann: We have a planned shout-out, don't worry.

Katrina: Oh good. [Laughs] I still think getting in the bookstore is the best way but it's true not everybody is near an independent bookstore that has their finger on the pulse. So in the absence of that I'd say get on the Internet. Susan Bernofsky, a great translator, she translates Kafka, Robert Walser, Yoko Tawada who's a really interesting Japanese-German writer, Susan Bernofsky has a blog called TRANSLATIONiSTA and that has all kinds of information on what's going on in the translation world. That's a great go-to. The Three Percent blog, they sponsor a translation award and they also do a lot of highlighting of all the long lists and short lists. They have a podcast where they talk about a lot of books in translation. I think Lit Hub has actually done a good job of doing these roundups of certain writers that you've never heard of before that you should be reading. They do a great job of kind of sifting through a lot.

And I think also awards are . . . they're obviously a subjective measure of quality but I think when you look at the long list and the short list of awards like the National Translation Award, the PEN Translation Prize and the National Book Award, actually just last year we instituted their translated book award. So they stopped doing that in 1983.

Ann: Oh wow.

Katrina: So I think the fact that they brought that back in 2018 is definitely a sign that people are more and more taking translation seriously and wanting to put more focus on books from elsewhere.

Ann: I love that. Katrina thank you so much for being on the show.

Katrina: Thank you Ann. It's a pleasure.

Ann: If people want to find your work and works you have translated what is the best way for them to do that?

Katrina: They can go to my website katrinakdodson.com. It's funny, to be honest I've only translated one book-length work but it was a big one. [Laughter] 40 years of short stories written by Clarice Lispector and so that took me a very long time so it almost feels like six books in one. That's the big one, and I've done other short work which is making me think I need to go update my website now. [Laughter]

Ann: Everybody needs to update their website all the time. It's a forever to-do list item.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: Ugh, shout-out to all the translators out there. Especially the women translators. Thank you for all of your tireless work.

Ann: Yes, and shout-out to the act of translation and the interest in it every month of the year. Truly.

Aminatou: Where will I see you Ann? I'll see you at the library?

Ann: Ugh, you will. You will always see me at the library.

Aminatou: Bye boo-boo.

Ann: Bye.

Aminatou: You can find us many places on the Internet: callyourgirlfriend.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, we're on all your favorite platforms. Subscribe, rate, review, you know the drill. You can call us back. You can leave a voicemail at 714-681-2943. That's 714-681-CYGF. You can email us at callyrgf@gmail.com. Our theme song is by Robyn, original music composed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs. Our logos are by Kenesha Sneed. We're on Instagram and Twitter at @callyrgf where Sophie Carter-Kahn does all of our social. Our associate producer is Jordan Baley and this podcast is produced by Gina Delvac.