Fall Books 2019

11/8/19 - We talk with authors Mary HK Choi and Liana Finck about their delightful new books. Plus, what we're reading: fiction, memoir and actionable non-fiction about climate change. Share your reading list on instagram with #cygbooks.

Transcript below.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | Spotify.

CREDITS

Producer: Gina Delvac

Hosts: Aminatou Sow & Ann Friedman

Theme song: Call Your Girlfriend by Robyn

Composer: Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs.

Associate Producer: Jordan Bailey

Visual Creative Director: Kenesha Sneed

Merch Director: Caroline Knowles

Editorial Assistant: Laura Bertocci

Design Assistant: Brijae Morris

Ad sales: Midroll

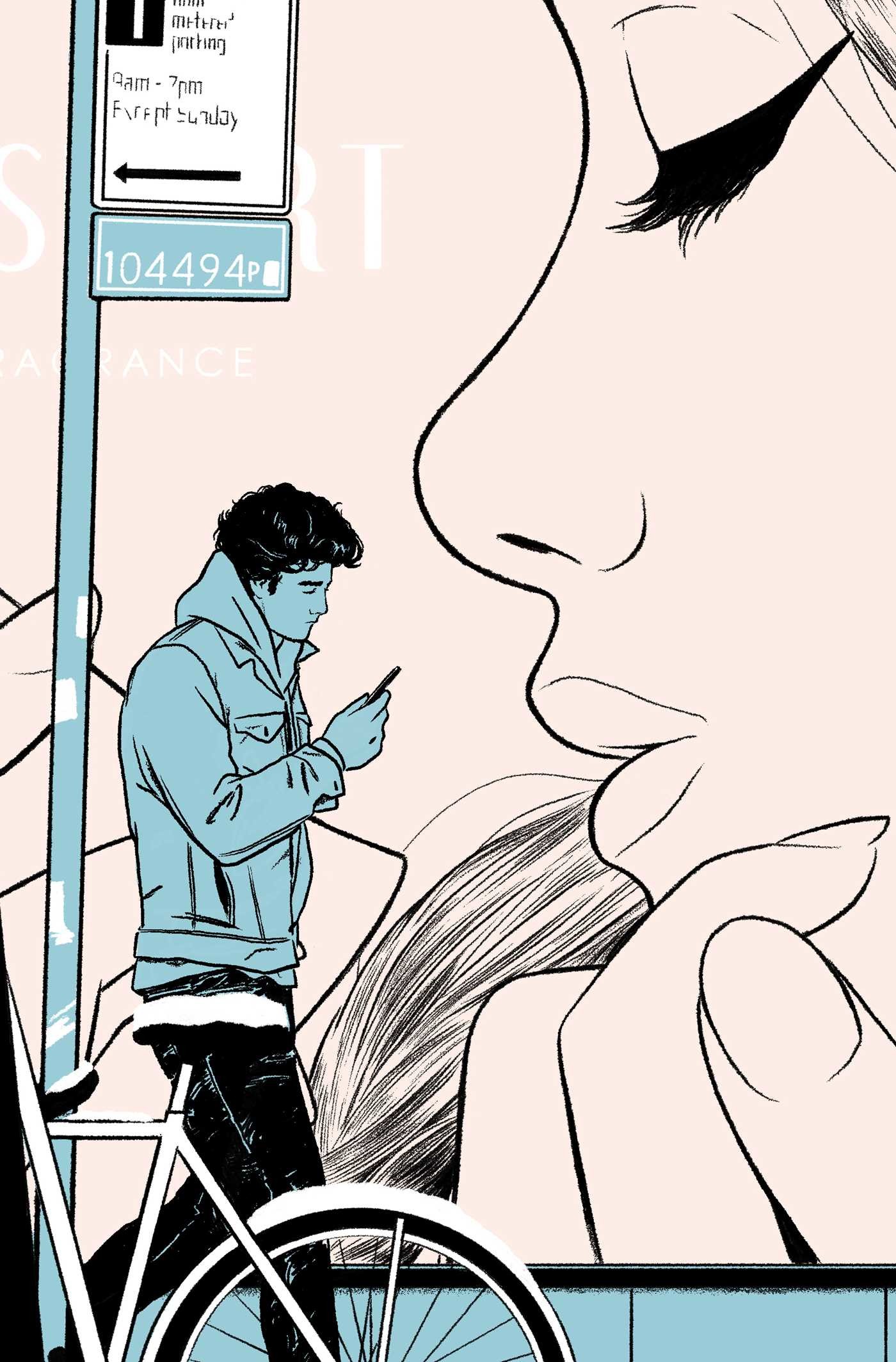

Episode image: courtesty Simon & Schuster

LINKS

Permanent Record by Mary HK Choi

Excuse Me: Cartoons, Complaints, and Notes to Self by Liana Finck

We are the Weather by Jonathan Safran Foer

Inconspicuous Consumption by Tatiana Schlossberg

A Year Without a Name by Cyrus Grace Dunham

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

Crazy Salad by Nora Ephron

TRANSCRIPT: FALL BOOKS 2019

[Ads]

(0:20)

Aminatou: Welcome to Call Your Girlfriend.

Ann: A podcast for long-distance besties everywhere.

Aminatou: I'm Aminatou Sow.

Ann: And I'm Ann Friedman. On today's agenda we're talking about our favorite books of the fall and our guests are authors Mary HK Choi and Liana Finck.

[Theme Song]

Aminatou: Hi Ann Friedman.

Ann: Hi Aminatou Sow. Are you ready to talk about books today?

Aminatou: Yo! We love books. Readers are leaders, y'all.

Ann: Oh my god, also our listeners are readers. I really -- sometimes I think about how in our last listener survey of all the interests we polled people about books was just far, far and away the top interest. And the surge of warmth I felt for this CYG community when I saw that percentage I was just like ugh, our people.

Aminatou: It makes me so happy. I was hanging out with my friend and her baby recently, and like truly a baby -- a couple months old -- she was like laying on her back, a baby, and had a book page open. And I was like you know what? All my friends are readers. I love this. [Laughs] That image just slayed me.

Ann: You're like even my two-month-old friends are readers.

(2:00)

Aminatou: Ooh, I was so excited to talk to Mary whose new book Permanent Record is out now anywhere that you buy books. And previously Mary had written another great novel called Emergency Contact so if you read that you're definitely going to love Permanent Record. And Mary is just -- she is just one of these supremely interesting, fascinating, thoughtful people and so to have her be writing books for any age group I think is so . . . it's so perfect to me. I'm like you could be writing books for toddlers and I'd read them. And one of the reasons I think I respond so much to her writing is that she's someone who just really thoughtfully engages with young people and with technology and use of technology, like what are our feelings about fame in general and what are our feelings about notoriety? Also she writes about food in a way that I really love and appreciate. I'm just really happy that she writes.

Ann: I cannot wait to listen to this conversation.

[Interview Starts]

Mary: I'm Mary HK Choi and I'm the author of Permanent Record.

Aminatou: I'm really excited to talk about your book today because it's such a fresh, modern theme that touches on so many different issues and we're going to dig into that. But before we do I really want you for the audience to say the name of your main characters out loud because it makes me so happy.

Mary: Okay. So it's Liana Smart is the pop juggernaut who is the love interest among many, many things. Far be it for me to be reductive about her. And Pablo Neruda Rind, it's a bit of an albatross literally speaking, but that is our main character. He's mixed Pakistani and Korean and he works in a bodega.

Aminatou: You mean a high-end deli? Excuse me.

(3:50)

Mary: I do. A Korean-owned 24-hour deli with macha Kit-Kats.

Aminatou: This makes me happy for so many reasons. Can you talk a little bit about where the idea for the book came from?

Mary: Sure. So much of it is about being a love letter to New York. I briefly lived away from New York which is my own bad. I tried it so to speak.

Aminatou: Welcome back. Welcome back.

Mary: [Laughs] And so much of what I missed was my bodega. It's this very specific relationship that you cultivate that gives you such a sense of belonging and makes your neighborhood distinctly yours. And there'd be moments when I was in aforementioned other place where I'd be like oh god, do I have to get into my automobile and schlep to a parking construction place and then like go to actual Target just for a two-for of Advil that I need for a vague headache? Like the inconvenience factor was just -- it dismantled me.

But a lot of it too is just like New York. I love the people here. I love that, you know, there is this kind of mutual Stockholm syndrome that we're all experiencing in that like New York is so inhospitable to humans and it's sometimes the unkindest place you can live and try to get on mass transit at. But I love the attitude it engenders. I love that no New Yorker doesn't have a hot take on absolutely everything and I even like the way when we smell something suspicious we immediately go to Twitter. [Laughter] Or like the group chat. And, you know, we just really hold each other down and I think that a lot of it is, you know, so many different communities have a scarcity mentality and they have that sort of barrel of crabs thing. I'm not saying New York is immune to that. In fact it's kind of concentrated in a lot of ways. But in sort of scrabbling for finite resources we end up lifting each other up in a really big way.

(5:45)

You know, and I know you appreciate this but New Yorkers have so much financial transparency and I always thought that was really important to talk about in fiction for young people. Because what else becomes more coming of age and more debilitating and more terrifying than money? Especially money in New York.

Aminatou: Right. And the thing I really appreciate about this, everybody who is listening to this who has listened to a book episode knows I struggle a lot with fiction because that's my bad. Because I don't have an imagination and I'm empty inside.

Mary: [Laughs]

Aminatou: But every time I read fiction I'm like oh, this is how the other half lives? No wonder they're much happier and smarter than me. Flex your imagination muscle. Thank god.

Mary: Well I mean flights of fancy are nice because you're like oh, let me leave here. [Laughter] You know what I mean? Then you're just like Kanye bear in the sky.

Aminatou: It's true. But the thing that I really appreciated about your novel, Mary, is that you write so specifically about that time between high school and the end of college where you are just a ball of confusion and you're trying to figure out who you are and some of it is hormonal, some of it is just time and velocity and all these things. But it's such an intensely confusing time that once you're removed from it it's really easy to forget.

Mary: Oh totally.

Aminatou: To just be like oh, like that -- you're like I have put that PTSD in a box and we're just going to bury it and we're going to pretend it's not happening. But I had such an appreciation for that of like this is really fucking hard and also it's hard for people who are not white in a very specific kind of way that also we never talk about that nuance. We're all just trying to find ourselves here and this shit is hard.

And so I just really -- that was something, like that was really evocative to me and I was really struck by how alive your characters are, specifically Pablo. This is a real person. This does not happen all the time with a person who is not white in books.

(7:50)

Mary: Well right, we all contain multitudes. And I think a lot of that, specifically if you have any melanin quotient within you, it's like a coming-of-age that happens with all of us especially as creative people that I think has to happen twice where you sort of come of age and become like an adult and by that it means that you're kind of struck with this crippling impostor syndrome because you have so much expectation of what adulthood would feel like.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Mary: And oftentimes you fall so short of that in terms of how you feel inside. And, you know, the whole thing about my characters being robust so-to-speak is I do delve a lot and stay inside and analyze a lot of the inferiority and what you're actually experiencing when you are just fraught with this existential freak-out. Because, you know, in so many ways especially with the amount of pressure that goes into college these days where that pressure is applied from such a young age you're conditioned -- it's kind of like Eye of the Tiger. It's just like get into a name brand school then you will have arrived. And I think a lot of people, once they get to school, they're just like oh shit, I still feel like me. It's kind of like when you're little and you have a birthday and you have all this expectation that you'll feel different by dent of another 24 hours and you're like wait, I still feel the same as I did when I was yesterday years old.

Aminatou: Big scam.

Mary: Big scam. Huge scam. And, you know, the whole thing -- I definitely had to get to a place where as an immigrant and as someone who actually grew up in a colony which is such a bananas thing to actually think about because . . .

Aminatou: Yeah, you grew up in Hong Kong.

Mary: I grew up in Hong Kong as a Korean going to British school. It's really, really confusing. And it's not even just the acceptance of self insofar as oh, I realize I'm Korea and oh, I accept this and I'm becoming more comfortable about being Korea and what that means for my identity. It's kind of like you get to a place where you have to sort of reclaim what it means to be a Korean artist and an East Asian person and a person who is part of the larger Asian diaspora and what that means.

(10:10)

I'm not saying like oh, until I was this many years old I thought I was white or aspired to be white. Like that's such a reductive thing that's often foisted on us by like the white lens. It's more that just there's this moment where in my experience I was unused to being the protagonist of my own life story. And I think that really does happen to a lot of people whose parents experience such a different upbringing and for who English might be their first language but it isn't of their forebearers. And there's always this schism of like code-switching not only class-wise but also the way you speak to your parents versus the way that you speak to your friends versus the way you even speak to like figures of authority in your friend or school world.

And so with Pablo, you know, as a kid who's also mixed he's having to sort of reckon with what parts of his parents' identities he can claim. And so there's a lot of things that happen to him that I think a lot of people can relate to. It's like when you are in a position where say you're at church with your mom or like some sort of place of worship and it's majority the one kind of minority that you are. Then you're like pop quiz, what's going to happen? Is someone going to ask me something? Is someone going to say something in a really offensive way because we're all the same?

Aminatou: Yeah.

Mary: In that over-familiar way. So Pablo does go to a wedding with his father and he immediately has this moment of panic that he doesn't speak or do. And, you know, he has the same thing in Korean as well and I think that's such a part of a mixed kid experience but it's such a part of the New York experience.

Aminatou: Yeah.

(11:55)

Mary: Because we are all such a mélange.

Aminatou: I mean I feel like that's putting it mildly. [Laughter] Yeah, I want to stay on this theme of family because another thing I was so struck by is the family members and the relationship with Pablo's family, those things are all fully-formed as well. The lazy version of this in the movie is you see a friend for two minutes then there's some type of plot device.

Mary: Right.

Aminatou: Then it's the same thing with the parents or the same thing with the brother. And here it's like no, no, this person, he's a member of his family and you get to meet his family and you get to understand these really complicated immigrant dynamics that he is having. And so I just -- I really want to hear a little bit more the process behind that of creating that world for him.

Mary: So in my first novel Emergency Contact it was -- all I knew about the mother/daughter relationship is that I wanted it to be a little bit like Lorelai Gilmore and Rory Gilmore or like Edina Monsoon and Saffy Monsoon from Absolutely Fabulous.

Aminatou: Amazing.

Mary: Where it's kind of this upending of the normal dynamic of what you would expect from an immigrant, especially East Asian mother/daughter scenario. But for Permanent Record I did want to explore a little bit of like this notion of a tiger mom which is such a pat stock character type. But I wanted to sort of peel that away a little bit so it's not just this incredible pleasure and this white-knuckled sort of guilt-inducing thing of you've got to get to this kind of story. You have to be a doctor or a lawyer. Which the thing is that is a dynamic that certainly appears within immigrant communities. But the thing I wanted to also question was like why can't I have this in this book without it being reduced to that?

(13:50)

Because I'm like for crying out loud, I live in New York. I have a lot of minority friends. I have a lot of immigrant friends with immigrant moms. Lawyers and doctors, that's like literally every immigrant. It's big with Haitians, you know what I mean?

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Mary: It's big with everybody.

Aminatou: Big with all of us.

Mary: Nigerians, it's like big with everyone. So I wanted to take that. I wanted to sort of peel it back and explore the dynamic between a first-born son and his mother and just reveal a little bit about what the actual motivation behind that is which is what it is for a lot of people which isn't they don't want to have clout about their expensive kid; it's they want you to be safe.

Aminatou: Mm-hmm.

Mary: And so I wanted to explore some of that fear between Pablo's mother K or Kyung Hee and him and what her expectations are as a doctor but then also I wanted to sort of explore a totally different dynamic with his father, you know? Bilal is super wavy and he went to Princeton and he did all the things and his family kind of -- they're kind of estranged because he didn't pursue a typical marriage or vocation. And I wanted that to be really, really specific and I wanted to interrogate some of that sort of masculinity and like without it turning into any sort of weird, patriarchal thing. It was really, really important to me if I was going to write a male protagonist that he be very tender, that he be very confused, that he be very anxious, that he not be so caught up in, you know, masculine foils and what that means because I know so many people in New York -- and this is very much a love letter to those guys too -- where they're all really evolved. And I have that experience with a lot of my male friends here, especially if they're artists, especially if they're really close with their parents and families and the women in their lives.

(15:55)

And so that was also really important for me to have, not to have this like lapsed Muslim father who was just like this one type of way. Bilal is so, so funny in that he's had 19 different jobs because he just hasn't had the one that most speaks to him and he really moves with spirit and he's really into holding space for his sons and he's really into affection and he's effusive and demonstrative. And that's another thing about writing fiction that is so beautiful is that you can create these people who not only define archetypes or stereotypes but are like just the best kind of people that are also deeply flawed.

Aminatou: Yeah. I mean and just again complicated people. I love it.

Mary: We all are, yeah.

Aminatou: We are but we're not allowed to be in so many scenarios right? And so I think that's . . . I really hope that's something that speaks to so many people and I know that it will.

Mary: I mean that's a part about writing for a younger audience that I do take really, really seriously. I do think there is a very, very large service aspect to the privilege of getting to write for people who are voracious readers of this age group. And by that I'm not sitting here being like oh, I have delusions about the fact that all my readers are in college or all my readers are in high school. YA is such a huge, huge readership. But I do do school visits. I do visit a lot of book fairs and things like that that are geared to teens in high schools largely. And I just want . . . Permanent Record is all about failure and I do think there's so much pressure applied to young people these days to succeed in these very, very large ways.

(17:45)

Like I think that one aspect of social media and, you know, the Internets is that you're exposed to so much and it's so beautiful except you're also exposed to certain things that you could voyeuristically sort of want and aspire to that are so, so rarefied. Like I'm not saying that Instagram is just advertising for the 1% but you are scrolling mindlessly through very, very rich people's stuff as well as your friends as well as the memes. What that does a little bit is I think it sort of is this distortion field that skews what you think the expectation is for how success and ambition is defined.

And I just wanted to be clear that you are going to make so many mistakes and you do feel as though you are a little bit in front of an audience as to your own failures, especially when there's so much pressure to edit yourself a certain way or carry yourself a certain way or delete all your Instagram grid versus your stories to be a certain aesthetic or stuff like that, to only have the most crystalized, distilled versions of your perfectest moments. And I just want to keep sort of harping on this notion that in order to find any learning, in order to find any success as defined by what makes you happy, you're going to make so many mistakes and you're going to fail a lot.

And I think that a lot of young people, especially from just even talking to them, but also every single poll, it's like there's such a premium placed on success that I think it actually curbs the willingness to attempt something. And so I do think that a lot of us, since time immemorial as it comes to teenagers and coming of age, we are trying to figure out what it is we want to do and we want to be. But it's just more expensive than ever I think emotionally to try something. Life in a lot of ways is surprisingly long when you look at it in terms of how much iterative learning there is to be done.

(19:55)

Aminatou: Right. I think what you're saying about social media is so important and is like a message that is so at the core of this book, right? And this thing that you're saying about just having access to rich people's stuff, like I always joke that what I really want people to put in their bios is how much money they have, how much money their parents make. [Laughs]

Mary: Totally.

Aminatou: And tell me your race so that way we all know what's going on here. But your book is not a romance book which I've been very frustrated hearing people -- like somebody tried to sell it to me as like a romance. It's like no, there is a romance at the center of this book but it is not a romance book. But the thing about the relationship that unfolds in this is that it really is one of class warfare.

Mary: Absolutely.

Aminatou: Where somebody gets to see the other side of how the sausage is made. And I was so -- you write about it in these very jarring kind of terms where you're like okay, great, you can go from this moment where you're just a kid in a bodega to being in a private jet. That is such a New York weirdo experience that can happen to someone. But also the whiplash of that is something that if you do not process together or you don't process it out loud it will eat you up. Like what does it mean to finally get context for how somebody else has power and how they have money?

Mary: Right. And that's the thing about class that's so gnarly. It's like you can be invited into these very, very special places and you can be like ooh, I'm amongst only a handful of people that have seen this side or whatever. But the whiplash of how transitive properties don't apply when it comes to both fame and money . . .

Aminatou: Oh my gosh.

Mary: Just because your friend knew this famous person and you happen to be sharing space with that famous person doesn't mean you can then go up to them. And it certainly doesn't mean that because you once hobnobbed or conjugated a special nighttime verb with a famous person, it doesn't mean their fans are then going to come after you and give you free shit. You're just a tourist and you don't even have your passport into rich people land just because you've been there once. And it is always darkest after the fireworks. And I've also been in situations where you might be in like the tractor beam of a famous person's attention and then when it sort of leaves you're like oh, it's cold. [Laughs] You know what I mean?

Aminatou: Right.

(22:15)

Mary: But that stuff isn't going to sustain you. It's kind of like -- I liken a lot of this love story, you know, people have accused my books of being a little bit like oh, nothing really happens. It's like hmm, not wrong. It is contemporary and it is kind of a quieter story. And I keep using this analogy, but I want all my stories to be recognizable to a point where Mark Ruffalo could be in them.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Mary: Where truly the biggest steak or the [0:22:42] begins at the kitchen table, you know what I mean?

Aminatou: I love this.

Mary: It's just like interiority is important. The sort of scale of the steak when you are a certain age, like things experienced for the first time feel seismic. That's how big they feel. It doesn't matter how small it is by the time you're like 55 and you've experienced the world. It's like that level of proportion and scale is something that I really, really like to look at. But yeah, like most of life -- and I think anyone who's tasted any success or even experienced any really big setbacks -- it's like most of life is that awkward 45 seconds of the movie Graduate after they get on the bus where they're like "We're strangers. It's weird now and it's awkward." Like most of life is that in-between nebulous space.

Aminatou: This is why it excites me that you write -- I hate this term -- but like ordinary people and ordinary experiences because I think two things are going on. One is that, you know, usually people like us only get written about when you do a superhero kind of thing.

Mary: Oh sure.

(23:50)

Aminatou: Like that's the kind of person you have to be. It's like why can't we just be like regular people? But I think also just exploding this idea that there is -- you know, that you go from this high experience to high experience to high experience and that's how you arrive somewhere. And it's like no, life is like some hard work and a lot of flukes a lot of times where . . .

Mary: And so much waiting.

Aminatou: So much waiting. And life just happens in those moments, like in those moments where you think that nothing is going on. It's like no, that's the difference between will you be at an important fancy thing the next day? A thing you did not socially engineer yourself.

Mary: Right.

Aminatou: Will you meet someone that can change your life? And I don't know. Sometimes I think that this is the trap of living in a big city, you know, is you think there's some sort of weird social engineering that you're supposed to be a part of, that it's that. And that's not how it works.

Mary: Right. Well and it sort of creates this weird suspension feeling of like almost making a moral issue out of everything where you're like how am I trouncing my own upward mobility by deciding yes or no to any number of decisions you're faced with in a certain day?

Aminatou: Yeah.

Mary: And going back to your point about social media too it's like I love the idea of potentially having like, you know, everything you've earned in your savings ratio, in your 401(K), and how rich your parents are, how much of that is a trust fund on your bio. But it's also like anything to do with a celebrity and aspiration so much within a large city and social media. It's like that whole compare and despair thing where it's like you are comparing your insides and how you feel in your lowest times to someone's curated outside. This one finite thing of a sheen of veneer of a hologram that you can never know what they're going through. And it's like yeah, I think that that casts such a pall on how you define your life's work and your aspiration and who you want to be. And that distortion is just so, so hard to get away from no matter how old you are. And I think that a lot of like . . .

(25:55)

And I'm not saying this book is prescriptive but I want a lot of inquiry to start happening the younger you are to sort of fortify yourself a little bit when you're older so that you can be like oh, I do not have to define success by these external mores. I know where my due north is and I'm the only one who can define what makes me happy and I can be the only one to define what it is I'm going to do.

Aminatou: Right. And also just, you know, I think that this particularly I got as an insight through Bilal, the father character, in really thinking about what it means to just submit to time, to your life, you know? And instead of worrying about why am I not 30-under-30, why don't I have the job my parents want for me, you know, this moment where you're like 20-something. I'm like you're literally a child. Nobody cares about your contribution to society or the world. It's why when you start your first job they only trust you with photocopies. It's like you don't know how to do anything.

Mary: But that's the capitalist scam though.

Aminatou: But you don't know that.

Mary: It's like you sort of like, you know, brainwash kids into thinking that optimization is what they want. And then that's how you can squish them and get as much marrow out of them until they're just husks that are entirely replaceable. That is the scam, it's the optimization scam, and it happens when you're young. And that's why when you're again in your 20s you're like "Oh no, I only have a TEDx talk. It's not a real TED talk. At this rate I'll never get Davos by the time I'm 29." You know what I mean?

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Mary: And these feel like real things that are foisted upon people and received by people and foisted upon themselves. And it's like that is really scary to me, like how are you going to know what you want?

Aminatou: Right. And I think that, you know, the answer to everything is time right? If you survive you are probably going to be fine but you have to survive.

(28:00)

Mary: And you have to surrender in order to survive with grace without completely cannibalizing yourself. Like, you know, the thing that's helped me a lot and it's something that I was only able to write, for a long time I was like oh, god, I feel like such a fraud that I'm writing YA at such an elevated, advanced age. But now thinking about it there's just a lot of insights that I didn't have access to at different points in my life where I was a lot more like in my addictions, in my self-obsessions. And so much of what I've learned in the last few years, especially as I write a creative pursuit that I then expose myself in like revealing to the world and being like I hope you love this tender, molten core of my psyche, a lot of what I just figured out or have been instructed by or what's been led to me I guess is believing that time is on your side. And not making yourself feel emotionally and psychologically and spiritually late for deadlines that you are not the one that made in the first place helps you out. Either you are right on time because the universe is a benevolent conspiracy to see you do well and you're ultimately taken care of or you're just running around to things that you don't even know if you had any agency in deciding you were late for.

And that's a really beautiful thing about time and just being really gentle and hydrating and trying to sleep and just showing up for yourself and the part that you can do that is in your control. That's all it is. And it's -- that's like a daily thing and you can't super worry about what's down the line.

Aminatou: That's so beautiful.

Mary: Thanks man. [Laughs]

Aminatou: Permanent Record is out now wherever you buy books. Buy a copy for yourself and for a young person that you know or a person that needs to stay young and Mary thank you so much for everything that you do.

Mary: Thank you.

Aminatou: It really was the treat of my month to read this book so thank you.

Mary: Yay! Thank you.

[Interview Ends]

[Ads]

(33:55)

Ann: So I talked to Liana Finck who is a cartoonist and an illustrator. She's been contributing to The New Yorker since 2015 but it's funny, she's sort of like "Oh yeah, my funny -- air quotes -- work goes to The New Yorker then my super real thoughts about sexism and the various joys and indignities of being a woman in the year 2019 go on my Instagram." So it's sort of like The New Yorker gets this skim off the top that is sort of maybe safer for that audience and then if you really want to go deeper into her psyche Instagram is the place. But she has a new collection called Excuse Me: Cartoons, Complaints, and Notes to Self that is out now. It is largely autobiographical. It's organized kind of by different subjects. But I really like her work that feels more observational of like let me just give you a snapshot of what it feels like to be a woman trying to have a solo moment in public and be constantly interrupted. Or let me give you a snapshot of the kind of spinning out in my own brain about something that on its face should probably be simple.

And I also really love her drawing style which is not like a classic newspaper cartoon, really stylized clear lines. It's kind of squiggly. All of her human figures are a little like wobbly blob-like which I love. [Laughs] And yeah, in general I really just appreciate it as a vehicle for this like hyper-specific to her perspective of the world which sometimes overlaps with things I have felt or happened to me and often does not. And I appreciate it in both cases. But anyway, she's lovely and I spoke to her in person in Los Angeles when she was on book tour.

[Interview Starts]

(35:45)

Ann: Thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Liana: Thank you so much for having me.

Ann: I want to ask you about this idea that occurred to me when I was thinking about your book and thinking about this interview which is like is reading your book an experience for me what it was like for some women to read Cathy 30 years ago and feel really seen? [Laughs]

Liana: I so much wonder. I have so much to say about Cathy. I didn't grow up with Cathy. I've come to appreciate it as a grown-up. I grew up with the Times. My parents refused to get a newspaper with cartoons in it and I think I wouldn't have loved Cathy when I was a pretentious teenager but I love it now as a woman of the people and I really appreciate it.

Ann: Yeah. I guess I just mean -- and maybe I should clarify what I mean by that -- is I assume there was some woman who's in the target Cathy demographic who was just reading it and like "Yes Cathy, I feel the same way about chocolate."

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: And it's more that experience where I feel like I'm your target demo.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: And when I look at it I'm like yes, that's exactly how I feel about men's emotions and walking down the street. [Laughs]

Liana: Thank you. Thank you, I do feel that way about a lot of Cathy-like things. I weirdly feel that way about Bridget Jones's Diary and Nora Ephron.

Ann: Yes.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: So yeah, so I came in contact with your work first on Instagram which I think maybe a lot of people do these days?

Liana: Yeah. Thank you.

Ann: What's that like?

Liana: It's nice. I find that the people who like me on Instagram are also people who I would like and do like I think 100% of the time and that's really unusual. I don't . . . I still don't really know if I have a New Yorker fan base but if I do I think they're not necessarily people I would feel comfortable chatting with.

Ann: [Laughs]

Liana: I think New Yorker cartoon fans are kind of like New Yorker cartoon characters in they're fun to watch but not fun to talk to.

Ann: Yeah. When I see your work in The New Yorker it feels like seeing a teacher outside of school or something where I'm like "Oh, you're here too." [Laughter]

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: For someone listening who has never seen your cartoons how would you describe what you're dealing with?

(37:45)

Liana: They are . . . so I've come to a certain realization which is that they're -- I've substituted the funniness in New Yorker cartoons we hope with directness. I've found that a single-panel cartoon can be direct kind of the same way, it's funny, but whereas New Yorker cartoons are a one-two punch with a setup and a punchline like a Jerry Seinfeld joke what I do on Instagram which is less funny is just a punch. And they're very autobiographical and I use them to work out problems that I'm dealing with in my brain which are usually very circular. But I find that when I draw them, especially if people see what I've drawn, somehow the circle is broken and the spiral evolves. So I deal a lot with . . . I have dealt a lot with dating which has evolved luckily.

Ann: Your dating experiences have evolved? Or the way you deal with it?

Liana: Yeah. Well the way I've dealt with it has evolved but also I'm no longer going on first dates because I'm in a relationship so that's a new canvas to paint I guess. And I also talk about being very shy and being kind of -- there is no more specific word I want to use than weird, slightly weird. And I used to have an eating disorder and I still think about food in a very concrete way, in a troubleshooting kind of way, so I talk about compulsive eating in there and stuff. What else? Oh, a lot about sexism. I think the whole thing can be defined as little ways that people are unfair to each other and trying to uncover them.

Ann: Yeah. There's something about the single-pane cartoon in the way you in particular distill what might've otherwise been a fleeting moment of sexism I guess is maybe how I would describe it that I very much appreciate.

(39:50)

Liana: Thank you, yeah. It's hard for me to let go of little things so I guess all the cartoons are things that one should just let go of that I have penned down and then can let go of.

Ann: Right, after you slow down and memorialize it and say that it happened. Then you're like okay.

Liana: Yeah, yeah.

Ann: Oh, and I heard you say -- and also sexism -- I was thinking about this cartoon of yours that I really feel compelled to share it every single day and I don't but the group of women dancing around a man's feelings. [Laughs] Is it a group of women? Women, just women.

Liana: I think that was women like . . .

Ann: Yeah, please correct me.

Liana: No, I don't remember.

Ann: Tiptoeing, yes.

Liana: Tiptoeing. Yeah, that's it. Yeah.

Ann: Women tiptoeing around a man's feelings. And there's something about the combo of that and your drawing style that feels very ancient cave art to me and I mean it in the best way.

Liana: Oh yeah. Did you know the cave art -- I don't know if this is true but I've heard that it was made by women a lot.

Ann: Oh, I did not know that.

Liana: Yeah. I don't know if it's true.

Ann: I mean who would've taught me that?

Liana: I know. Not men.

Ann: Right.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: I would love to hear you talk a little bit about the process of what made it into this book and what didn't.

Liana: This book was almost all taken from Instagram although I redrew everything for the book because I hadn't archived my work and I never will because it's much more stressful to archive work than to make work. But anyway I chose the cartoons with the help of my editor Andy Ward at Random House. He's very hands-on and he was very helpful in helping me winnow them down. And it was also I think his idea or my agent Meredith Kaffel Simonoff's idea to put the book into chapters instead of chronological. I was kind of championing for chronological but I could see how that would make someone weary. It would resemble a circular thought where you're like men, food, anger, men, food, anger, instead of just like men. Food. Anger.

(41:50)

Ann: [Laughs] Yeah. Well and I also think it helped me understand as someone who like I said follows your work on the Internet where I maybe do get it more chronologically or get men, food, anger, men, food, anger.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: It helped me say like oh, these are like broad themes you're exploring.

Liana: Yeah, yeah.

Ann: And I was wondering if we could do an open the book and have you read and describe what the image is for a couple of them.

Liana: Yes please. This one is called The Two People Who Get It and it has a picture of the character who's my avatar who's actually based on my former dog, not on me.

Ann: [Laughs]

Liana: She had like long, blond ears. So anyway, so A) You, that's one of the two people who get it. And B) A guy you only know through the Internet.

Ann: Wow. [Laughs]

Liana: Thanks. That's to describe the feeling of really vibing with someone who you haven't met yet and it's such a beautiful feeling to write about and it's so dangerous in real life and you can only feel it so many times before you get jaded.

Ann: Right, and start to be skeptical of it.

Liana: And then I have one that's called being "Single But Open" and it has a picture of a fishing line with a hook and then my avatar character dangling off the hook and she says "Now I just wait." She's often like -- maybe Cathy has this too. She's often kind of placidly contented when she's actually in a very bad situation. And then I have one that was a rejected New Yorker cartoon so it's actually "funny" where it's a picture of a man very gallantly putting his jacket over a hole while a woman waits and it says "A gentleman throwing his jacket over a hole for a lady." She's going to fall in so it's not that gallant.

(43:40)

Ann: It's so funny because that one I get. I get what you mean when you say it's a funny one. But I'm also just like dark truths. Like that's more what I thought, a dark reality.

Liana: Yeah. Are you pro-men opening doors for women or no? Or people opening doors for people I guess?

Ann: Yeah, I'm pro someone who gets there first opens the door.

Liana: That's what I'm pro as well.

Ann: But I don't . . . I always judge men who seem put off by the fact when I get there first and open it.

Liana: Yeah, yeah. I encounter so few of those men I wonder. Maybe I'm just not even looking at them but they're awful.

Ann: Yeah. I mean it's a very telling . . . it's very telling. [Laughs]

Liana: Yeah. Can I make a shout-out to my friend?

Ann: Yes please.

Liana: Tahneer Oktsman. She's the one that introduced me to your podcast and turned me into a feminist.

Ann: Oh my gosh, wait, tell me more about how you know each other.

Liana: Okay. She's a comic scholar. She's a feminist comic scholar and I met her, she organized a conference when I was maybe 24 and I met her through the conference. And she was intensely feminist and I was just scrambling to get a date at that point which kind of precludes feminism in a young person maybe. I don't know, meeting her hastened the big change.

Ann: Oh my gosh, I love that.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: Shout-out to her.

Liana: Hi Tahneer.

Ann: Also just like feminist comic scholar, like yes. Of course. [Laughs]

Liana: Yeah, yeah. She's like of a different era and she belongs in -- like she needs to be in this era. We need her.

Ann: Wow. I was just reading, speaking of other new books that are out, Lynda Barry has this how to journal book.

Liana: I haven't read it yet but I adore her.

Ann: Yeah. And I also really like her but the book is really very how-to, you know? There's a lot in there about the way people like me who are not words plus pictures in my journal, I'm just a words in my journal person, have been separated from maybe an innate impulse to also want to draw. I'm curious to hear you talk about that, if you're a forever doodler who kept up and honed like that as a skill?

(45:52)

Liana: Yeah. I think I'm a forever doodler. I took a detour and went to art school and had to kind of throw away the polish I learned partly because I was never great at the polish. But just thinking that polish makes you a better artist I think is so gross and untrue. I also think that drawing is -- I guess I learned this from reading some secret letters written by Saul Steinberg that I obtained in a sneaky way that drawing is kind of the building blocks of writing, that we're just kind of inventing our own alphabet. And I like to think of it that way. To get pretentious again Kafka used to doodle and he also said that drawings were -- his people that he drew were like letters and I love that.

Ann: Oh wow.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: Sorry, you're blowing my mind with that.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: I have so many questions like how did you obtain these . . .

Liana: Oh, I will tell you. I interned for the Saul Steinberg Foundation when I was in college and it was a kind of weird under-the-table internship where I just asked for it and they didn't need interns but they took me on. And I was copy-editing a lot of letters that were going to make it into a book but didn't and I still have them and I probably shouldn't still have them but I share them with anyone who asks.

Ann: Oh my gosh, prepare for emails.

Liana: I am.

Ann: Unless you want us to cut this because . . .

Liana: No. Unless I get a cease and desist I'm going to continue to do it because they're so good.

Ann: [Laughs] I'm curious about whether there are times -- you know, the whole words plus images together which maybe I'm splitting hairs in terms of the Kafka words as images and vice-versa -- but if there are times when the words come to you first then the images follow or vice-versa where you're like oh, I just need to draw this scene then figure out the words for it later?

(47:45)

Liana: Yeah. I really do think of them as kind of the same thing. New Yorker cartoons, there's a divide in New Yorker cartoonists between the image-first people and the word-first people.

Ann: Oh?

Liana: And I do not think there is such a big rift between the two for me. But that said sometimes the words come to me first when it's a cartoon very much out of real life, like I had one in the book that was taken from something a man said to me on a first date which was "You can't be 5'5. I'm 5'5." So that was just quippy and I just had to make pictures so that it would be a cartoon.

Ann: P.S. it's very funny that you mention that one because I have a very tall body and men are forever asking how tall I am then disagreeing with me about my own height because they always inflate theirs by several inches. Anyway . . .

Liana: Right. They want you to be short -- wait, they want you to be taller because that means they're taller if they're shorter than you?

Ann: It's unclear. It's not exactly clear to me. But I do think that there's some aspect of "You can't say the same number I'm saying because I'm standing here and we're clearly not the same height."

Liana: Yeah, exactly. And they're usually shorter than you when they say that.

Ann: Exactly. [Laughs] Yeah, the male ego is one of the kind of aquifers that I feels like runs under this. Which is so funny. It's like yeah, it's a thing that we all have to deal with. So much of your book is about being a woman in a public space I feel like.

Liana: Yes, yes. A woman and a weird person. Yeah. I think I have like -- I need three inches between bodies of strangers whereas many strangers need half an inch.

Ann: [Laughs]

Liana: And that dovetails very nicely with being a woman because women are often given zero or negative-something inches in public.

Ann: Oh my gosh, how do you live in New York City if you're a three inches person? I'm like I live in Los Angeles. We're like a three miles place.

Liana: Yeah, I have some techniques where I kind of use my hands to describe the space I need around me.

Ann: You physically delineate the space you need?

Liana: Yeah. I've gotten better. I also have what I call the Queen of England move where I don't know if Queen Elizabeth does this but I imagine she does where I very graciously touch the shoulder of someone who's barreling into me.

Ann: Wow.

(49:50)

Liana: And if you seem gracious they don't have anything on you.

Ann: And it works? It shuts them down.

Liana: It actually works. Almost no one has gotten angry. I think a couple of people in the past couple of years have gotten angry.

Ann: Wow.

Liana: Yeah.

Ann: Wow, New York survival tip. I'm using that next time for sure. I would love to hear you talk a little bit about things that you have read in the not-too-distant past that you were like oh my gosh, I can't stop thinking about this. I have to talk about it with everyone. Or just, I don't know, churn it over and over in my mind.

Liana: Yes. I read Keiler Roberts' Rat Time. I love all of her work. I also love all of Gabrielle Bell's work. They're both autobiographical and they have a similar vibe so I don't like to mention one and not the other. My body Juliana Wang's book that you guys talked about on her.

Ann: So good.

Liana: It's so freaking good. I can't even describe it. I have a thing where I don't like to describe things that I love because I believe that they're magic, truly. It's a book of short stories based in -- many in Chinatown, some in China, about immigrants. But they're so perceptive and funny and brilliant and weird and vivid and her. It's like I'm with her but times a hundred and it's the coolest thing.

Ann: I love that. Liana thank you so much for being on the show.

Liana: Thank you so much for having me.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: Ugh, so good.

Ann: So good. So what else have you been reading?

Aminatou: I've been reading a lot lately Ann. [Laughs] Patting myself on the back. Here's what's on the bookshelf, the just read. I just finished reading Jonathan Safran Foer's new book called We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast. If you've read his previous book Eating Animals you understand that he's been having this longstanding conversation about what it means to be someone who cares about the planet and what that means for your food choices, right? And so I didn't read Eating Animals for a long time because I thought it was going to be -- rightly -- one of those books that was like stop eating meat. I enjoy a steak every so often enough that that was a message I was not interested in hearing.

(52:10)

Ann: My beef honey. My beef honey. [Laughs]

Aminatou: You know it. You know it. The anemia family.

Ann: I know.

Aminatou: And so I finally read Eating Animals years later and it's just like, you know, classic of the genre. When you fully understand the horrors of mass meat production you don't need to eat it. You fully do not need to eat it. The thing that I really enjoy about this new book, the We Are the Weather book, is it doesn't focus on factory farming and all of the scale of all of that. It really is about the environmental impact that a lot of the choices that we make at home have. So something as simple as eating meat and dairy, he offers a lot of practical suggestions for reducing consumption of animal products. I don't know. I just felt like it was a more subtle and a more stealth book. And the way also that it's gotten me to think a lot about, you know, just my own behavior in general. I say that I'm someone who cares about the planet. I stand Greta Thunberg hardcore. And yeah, there are a lot of things that I don't do in my own everyday life.

So I think that the approach, the approach that Jonathan takes in this book, is very measured. It's very moderate. And it's also I think that for people who think they're really inflexible it just lays out like a really good plan for you. Like it's not didactic at all. It's not judgmental. And it really, I don't know, cuts to that place of for the crowd who's like ugh, I love a hamburger so much but also the world is dying and falling apart like what can I do? I think that really thinking about that and re-framing from being like ugh, I'm such a hypocrite to actually what are practical, easy things that I can do is something that's really important. And also challenging yourself in every way instead of just running away from wanting to know about what the arguments are because you think that you're not willing to do the work.

(54:05)

Ann: Right. Or because of the very true statement that it's like oh, government regulation and what industries do has a far greater impact than what individuals are able to do which I don't see as a cop-out. I think everyone should still -- especially people who have the financial means to do so -- should be making better choices. But instead of just saying "Okay, well I've seen that this is mostly a thing that businesses are on the hook for . . ." Should not let you off the hook.

Aminatou: Right. I also think that purely separate from the argument itself one of the reasons I also really like this book is it's such a good study in how you write an argument. And so thinking about what are all the ways that you can change people's minds? Like some of those ways are being very rigid or making people feel guilty or making them feel shame. There's so many feelings that you can bring out. And I was like oh, there is a way to write a passionate argument in a way that really doesn't bring out negative feelings for the reader and so that's also something I've been studying a lot. And I was like great, I can hang with this.

Ann: I love it.

Aminatou: Sorry. Another book that I'm reading right now is called Inconspicuous Consumption: The Environmental Impact You Don't Know You Have by Tatiana Schlossberg who is a former New York Times science reporter. We love a science reporter. And so this book is also very good. Can you tell that I'm very worried about the planet Ann?

Ann: [Laughs] And rightfully so.

Aminatou: You know, some people watch horror movies. Not me. I just read about the planet. And she really looks at how all of our daily habits impact the environment. Everything from how you use the Internet to what food you're eating, driving and fuel, and a topic that is near and dear to my heart, to fashion, like the way you shop for clothes and the impact that that's having. And this book is weirdly very funny. There's a lot of self-deprecating humor. There's a lot of really in-depth research. And so you know how sometimes a lot of these science books, it feels like it's a hard read, like hard pill to swallow? This one is funny enough and written simply enough that it goes down very, very easy and so you don't feel like you need to know the inside and out of agriculture or transportation or crypto or whatever to get it.

(56:25)

My head is really in a like the world is burning place and who are smart people that are writing about this and also what can I do in my own life? So that's the reading zone that I'm in right now.

Ann: It sounds heavy but also good?

Aminatou: Yeah, you know, but it's a kind of . . . it's heavy but it doesn't make me feel guilty. I both need to hear the science and the whatever behind it but also really challenge my own habits every day. And I think reading books helps me do that.

Ann: There's also pure relaxation reading, but let's be real, anything that I'm recommending to a friend as something I truly loved is something that has also challenged me in some way probably.

Aminatou: True, true, true. What are you reading?

Ann: I am reading a pair of memoirs, or rather have recently read a couple of memoirs, which writing something -- like working on our book which is not a straightforward, exclusively a memoir but has a lot of those elements has been really interesting in terms of me reading other people's because everything I read is now the best book I've ever read.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Ann: Which is not to downplay these memoirs or these writers because I think they are actually very good writers but it's like trying to learn to play an instrument then all of a sudden you really appreciate the virtuosos. Where I'm like wow, we're out here just trying to get this book done and these people created art, you know? It has heightened my appreciation for other writers' works to attempt to write a book which is interesting.

(57:55)

So two of the memoirs I have read recently are A Year Without a Name which is Cyrus Grace Dunham's memoir and Carmen Maria Machado's In the Dreamhouse which Carmen was on the podcast, a different books episode, I want to say two years ago? Maybe early last year talking about her short story collection Her Body and Other Parties. And this new memoir In the Dreamhouse is a story about surviving relationship abuse in a queer relationship but it is also a story about kind of how we own our stories and come to own our stories. And the way we tell our story in different ways over time. Like in real-time we might tell it to ourselves and our friends in one way and leave out certain pieces, then in retrospect when we're talking about a thing that's happened in the past we can make it a horror story or we can make it a parable. We can really kind of choose to put the emphasis in a lot of different places.

And she's written this kind of structurally experimental memoir about the ways very complicated stories get told. And I think on both a level of feeling like the story itself is just profoundly important and profoundly important to informing a lot of the work that we collectively have to do to make everybody safe and healthy in the relationships they choose, but also important in the sense of really showing how complicated it is to have a lived experience of being in and then coming out of an abusive relationship. And I mean it was really just so good. There's even a twist, like narratively it's also extremely engaging which I'm making it sound very nerdy and kind of conceptual but I devoured it in one-and-a-half sittings -- I guess that's two sittings -- but you know what I mean. I read it really fast. [Laughs] And at one point I was just motivated to throw the book across the room because it was so good, just like dang.

Aminatou: Oh my god.

(59:45)

Ann: That is a very visceral reaction that I have when I read something that kind of checks all these boxes of like it is, you know, I think socially and politically important, culturally just so beautifully executed. Anyway I screamed. I really recommend it. I believe it is out as of early November. And I also really enjoyed A Year Without a Name. Not to give that short shrift but I think it was a very solid memoir about trying to tell a story about identity that is not like, you know, the hero's journey. Let's tick some boxes about drawing neat conclusions or having a rising action then a conflict and then a resolution. It's both of these stories and I lump them together mostly because I read them recently, not because they are both stories about very different queer experiences. But I do think they speak to the complication of being a human being and trying to make good choices for yourself and do right by yourself.

So those . . . I've been in my own little group of memoir. [Laughs] My reading group of one. And then also I recently have revisited Nora Ephron's Crazy Salad which I had not read in 20 years.

Aminatou: Oh my god, what a flashback.

Ann: And I was also, I'll be honest, partly inspired to do that by reading more modern stories about gender and how we think about gender because that book is a collection of columns -- she wrote a monthly column for Esquire in the early '70s -- and the book is a collection of those columns. And in the introduction to the original printing, I think it might've come out in the late '70s or early '80s, she was like "You know, I still stand by some of these and some of them I've moved on from whatever view I was espousing at the time I wrote this." But it is just an interesting time capsule on a lot of different levels in terms of -- like I love reading about the women's movement chronicled in real-time, you know? The women's movement as chronicled in real-time is so messy, such a hot mess. And it also was a good check on the narratives for how things are remembered or we can say we remember Betty Friedan is problematic. Like duh, I would definitely check that box in a multiple choice survey. But some of the actual details of the behaviors she got up to, I was just like wow, it's good to be reminded. And also good to be reminded of how far we've come in a nuanced understanding of what it means to describe a gendered experience of the world. And so I'm really enjoying it. I'm not saying I'm reading it uncritically but it is . . . I don't know. I really do -- I like including the occasional flashback in what I'm reading.

Aminatou: We love finding out what you all are also reading and so if you want to let us know, you know the drill. The hashtag on Instagram is #CYGBooks. I love to peruse and get inspired there and so can't wait to find out what y'all are reading.

Ann: Ugh, and I will see you on the Internet and in the library and in the independent bookstore.

Aminatou: You can find us many places on the Internet: callyourgirlfriend.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, we're on all your favorite platforms. Subscribe, rate, review, you know the drill. You can call us back. You can leave a voicemail at 714-681-2943. That's 714-681-CYGF. You can email us at callyrgf@gmail.com. Our theme song is by Robyn, original music composed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs. Our logos are by Kenesha Sneed. We're on Instagram and Twitter at @callyrgf where Sophie Carter-Kahn does all of our social. Our associate producer is Jordan Baley and this podcast is produced by Gina Delvac.