Pronoun Power

6/28/19 - How a functional piece of grammar says so much about the fight for gender equality and better representation for non binary and trans people. We learn about pronoun best practices and how progressive linguists are fighting for better words and more creative expression. If you’ve been wondering… is “they” a good stand-in when you don’t know someone’s gender or pronouns? How do I ask for people’s pronouns? If someone uses she/her does that mean she identifies as a woman? But isn’t “they” a grammatically incorrect singular? We get into all these questions and more.

Transcript below.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | Spotify.

CREDITS

Producer: Gina Delvac

Hosts: Aminatou Sow & Ann Friedman

Theme song: Call Your Girlfriend by Robyn

Composer: Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs.

Associate Producer: Jordan Bailey

Visual Creative Director: Kenesha Sneed

Merch Director: Caroline Knowles

Editorial Assistant: Laura Bertocci

Ad sales: Midroll

LINKS

GLSEN’s guide to pronouns for students and teachers has helpful guidance for everyone

More research and info from linguist Kirby Conrod

Follow Kirby @kirbyconrod

TRANSCRIPT: PRONOUN POWER

[Ads]

(0:45)

Aminatou: Welcome to Call Your Girlfriend.

Ann: A podcast for long-distance besties everywhere.

Aminatou: I'm Aminatou Sow.

Ann: And I'm Ann Friedman.

Aminatou: Hi Ann Friedman!

Ann: Hello.

Aminatou: What's the agenda today?

Ann: Okay, on this week's agenda we're talking about pronouns, a.k.a. the intersection of language and identity and how we refer to people and how we are referred to ourselves and kind of on a bigger level we're talking about why language is so gendered and what can we do about it?

Aminatou: It's a thing that I feel like people make unnecessarily complicated but also language is really important and matters and I'm really glad that we have experts who are coming on to talk to us about it.

[Theme Song]

(1:53)

Aminatou: Ann, why do we care so much about pronouns on Call Your Girlfriend?

Ann: It's important because A) we're word nerds and because B) the pronouns is the part of speech that refers to people, like the participants in the discussion, people who are actively doing things, people who are verbing in the sentence. And often in our limited language those pronouns come with certain genders and identity assumptions attached. They don't always line up with the person's gender identity but that's kind of the way a lot of us use them and the way many of us were trained to think about them. And so a lot of really important gender liberation work that's happening is taking an interest in pronouns and getting us all to pay a little bit more attention to how we're using them. Is that a fair summary? I don't know.

Aminatou: That's a fair summary Ann, you know? And I think a way to think about it is basically like, you know, it's how do we make gender-neutral or gender-inclusive pronouns for everyone? And it's really not that hard. It's like a gender-neutral or gender-inclusive pronoun is basically just a pronoun that does not associate a gender with the individual who is being discussed, right? Or that you are discussing with.

Like I'm such a nerd about this because Ingles is not my first language but I think about, you know, in French everything is gendered. A table has a gender. A computer does. Like humans do. And it's always very frustrating. But in my experience of incorporating gender-neutral language it has predominantly been in English and so it's something that I think a lot about because English is also not perfect. But English for example does not have -- like we don't have gender-neutral pronouns in English or we don't have . . . there is no like generic way to talk about an individual in the third person. And then there's also this dichotomy of always being like he or she. We very much operate on the binary which doesn't leave any room for other gender identities and that's just a source of frustration for a lot of people. And for me fundamentally it really is about boiling it down to what do people want to be referred to as, right? And that is just like a very basic point of respect that you should have for everyone.

Ann: Right. It's like what are the pronouns you want to be called by? Call me by my pronouns to paraphrase.

Aminatou: Call me by my pronouns.

Ann: An excellent film title. [Laughs] And, you know, I also think part of it isn't just thinking about it in terms of hey, are there some people who prefer a gender-neutral pronoun? It's also thinking about ways that the pronouns someone prefers might not exactly line up with their gender identity.

(4:35)

Like for example, you know, JVN -- Jonathan Van Ness recently came out as non-binary and said that he would continue to use he/him pronouns and that felt right but also that he does not identify as a man. And so there are things like that that complicate the picture as well. It's not just like hey, do you fit in category A or B? It's really just this question of what words do you want used in reference to yourself? And how can we make it easier for people to make that choice regardless of how they identify?

Aminatou: Right. It just makes me happy because it's the intersection of a lot of things that we care about. And, you know, as a different kind of word nerd from you this is also very exciting to me.

Ann: So I spoke with Becca Mui who is the education manager at GLSEN who is really ensuring that schools and students are getting a full and inclusive picture of all things gender and gender identity and she really gave me the 101 about pronouns and how we should all be thinking about them.

[Interview Ends]

Becca: I'm Becca Mui. I use she and her pronouns and I'm the education manager at GLSEN.

Ann: Awesome, thank you so much for being on the podcast today.

Becca: Yeah, thank you for having me.

(5:50)

Ann: Maybe this is a super, super basic place to start but especially because you are in this educator role I don't think you will hate a one-on-one question which is just why should everyone care about pronouns? Why is a pronoun actually something we should all be attuned to?

Becca: I love that question and I think it is really important and we get it a lot. You know, they're such tiny words and so we spend so much time thinking about them and a lot of our resources are based around why does this little word matter so much?

You know, really the basic focus of pronouns and the reason that pronoun visibility is such an important support is that when we're using someone's pronouns what we are doing is really assuming something about someone's gender identity. For example someone who uses she/her pronouns might identify as a woman but we never want to assume someone's gender identity based on their pronouns or their gender expression.

So just having some pronoun visibility and some understanding and a practice for inviting people to share pronouns is just an acknowledgement that we can't look at someone. We can't see what they're wearing, their mannerisms, or take any of those forms of gender expression and then make an assumption about how they identify or what pronouns they're using.

Ann: Right. And I sort of think about it on a base level of just like how do people want to be spoken to? Or how do they like to be addressed? And I don't know -- I'd be curious to hear your thoughts on that of whether that's like minimizing what is actually something a lot deeper or whether that is . . . I don't know. How do you feel about that framing of it? Because sometimes I think about that as being the most general way to say, you know, this is not about gaining knowledge about someone's identity, although it can be. Sometimes it's literally just how do people want to be spoken to?

Becca: Absolutely. And I think just affirming people when they decide what their name is, what their nickname is, how they want to be called, and how they want to be addressed. Those are all just basic courtesies that we can offer to people.

(7:50)

Ann: Right. I would love to hear you talk a little bit about best practices maybe in a more professional environment or in something like your email signature or in a social media bio because I am ashamed to admit it took me a very long time to put pronouns in my email signature. It took someone who I know and care about replying and being like "Um, this is kind of out of step with your professed beliefs that you don't say that." And weirdly I had had a mentality of oh, I don't work in an office. People who are emailing with me -- like my gender is pretty front and center on my website if you're emailing me as a stranger. I had sort of written it off as not necessary with me which I now find to be obviously not the case. So I'm curious how you talk about email signatures and why that's a good thing to do for everyone.

Becca: Absolutely. So around email signatures particularly GLSEN does have a statement that's also linked in our email signatures so that folks who are newer to seeing pronouns in an email signature can click on that link and just learn a little bit more. And it just explains why pronouns are important and why we're creating that visibility and gives a little more context for that for folks who are newer. So even in that realm just providing that kind of visibility and education for folks that may not be thinking about pronouns, having an email signature can be useful in that way.

We also found just as you were mentioning what we're saying about pronouns is not assuming, right? So when we don't have pronouns in our email signatures what we're saying is please use our name and kind of assume what pronouns you're going to use for me. So we just want to make sure that we're moving away from that space of just making assumptions for people.

Ann: Right. And I think that was a real shift for me of realizing not including them was essentially inviting assumptions not just about myself but about other people that might be giving or receiving emails, i.e. all of us.

Becca: Absolutely. And just something I think that also comes up for me. So I identify as cis gender which just means I was assigned female at birth and that's aligned with my gender identity so I identify as a woman. And I think there is a lot of work that cis people can do in this area and to be creating this visibility. I think sometimes it's easy for us to say, you know, this doesn't matter. I use she and her pronouns. That's probably what's assumed for me. But really it's something we can do as allies and we like to support this work by sharing our pronouns and making sure it's not just on the labor of folks that are gender non-conforming or trans or folks whose pronouns may not be what's assumed when people are looking at them to just be the only people bringing up pronoun visibility or the only people including it in their email signatures.

(10:20)

Ann: Right. I noticed that one of the tips on the GLSEN website is to practice and I'm wondering what practicing means in the context of pronouns.

Becca: One of the reasons that we recommend practicing is to really avoid misgendering. So that's kind of the experience of being labeled as something other than the gender a person identifies with and that's an experience that can be really harmful for people. And so we want to try to avoid that as much as possible. And so we just encourage folks to practice particularly around gender neutral or they/them pronouns. If that's newer to someone it can be kind of sticky at first and can be something that doesn't come so naturally. And so we just want to make sure that folks are in the habit of taking a pronoun that's being shared and using it right away and using it in a way that feels natural and right. And that may not happen in front of people all the time without some extra practice.

Ann: And so maybe you can give me an example of what that might look like particularly in the context of maybe like work or school. Not like, you know, you have a friend who uses they/them pronouns but let's say you have a new colleague and you're getting used to a pronoun that you are not maybe so familiar with or isn't rolling off your tongue quite so easily. What does practicing actually look like or what does that mean?

(11:40)

Becca: So practicing can look a number of different ways. One thing -- just as a simple practice that we encourage folks to do -- is if someone has come out to say that they're using gender neutral pronouns or new pronouns that are different than ones you're used to using for them you can take a picture of them and just say that pronoun and look at the person and practice sentences saying "She went to the store" or "I can't wait to see her today." Just saying those things by yourself can really help you that when you see that person you'll use the pronouns because you'll have linked it in your brain.

We also have a lesson for elementary students that we recently put out called Pronouns: Little Words That Make a Big Difference. And that lesson actually introduces they/them singular pronouns and has a game that helps students to practice formulating sentences with singular they/them and also just she and he pronouns.

Ann: Right. And one reason why I kind of harp on this practice question is because I am a word nerd. One thing I love about language is the way that something that can feel very foreign or like a slang term or a pop culture term or like a pronoun can feel so outside your norm that it's almost like a record scratch and then become such an easy part of your speech. People love to applaud that when it comes to text language or other -- you know what I mean? Maybe pop culturally. And I think that for me anyway thinking about that as inadvertent practice, right? Like when I type LOL. I had to learn what LOL meant, right? At some point in my 37 years on this planet. And just the idea of what sounds like "natural" to the ear or what rolls off the tongue being something that you can take an active role in cultivating is something that I think is very cool about language. And especially I bet you find that with younger people that you tend to work with.

Becca: Yeah, absolutely. And I think with younger people it's coming a little more naturally to them. I think these are things that they're able to kind of roll with. They don't have to work as hard to practice. But my work with educators particularly, educators that have been doing this work for a long time and might be newer to it, we really do have to work with particularly say English teachers to say like singular they/them has been put into the dictionary. It is accepted in APA format. This is a real thing that is happening that it's our responsibility to model in our classrooms and to affirm our students. That kind of work is really what I focus on just helping educators to understand these practices, understand the importance that these little practices and these affirmations can do for their students, and also just to help them feel comfortable in their own language when they're working with young people.

(14:10)

Ann: And that's really interesting too right? This idea of even -- because in my mind even if it were not dictionary approved it would be okay. Like language is a thing that's changing all the time. And yeah, I imagine that with say language educators or English educators it might be a harder pitch to make, I don't know. [Laughs] I would love to hear a little more about how this type of education works for you when you are dealing with adults like that. Like what are the things that you say to shift people's mentality about pronouns?

Becca: Absolutely. Well I think one of the first things that we do is just as we started here just talking about the importance. I think that it's not really on the radar of a lot of educators so sometimes just beginning there to say that we don't know how our students are identifying. We don't want to assume for them what their pronouns are and just explaining how it's such a small thing that can make such a big difference is really the place that we begin.

And we also ask for them -- they're creating a safer space for their students. They want them to be able to learn for the most part and so just calling on that drive that they have to reach their students and to connect with them and to affirm them is one of the ways that we encourage them to be able to put into some of these practices. And so in a classroom a lot of the things we're saying, it'll look a little bit differently. So we'll ask them to ask students to share their pronouns say on their worksheets at the beginning of the year and to make sure to kind of check in throughout the year with something they've identified because we know that pronouns can also shift and change. We also encourage the practice of just having pronoun pins or stickers available in the classroom that way young people if they want to share can share.

(15:55)

And particularly with young people but really with everyone it's important to understand that not everyone uses pronouns and not everyone is comfortable sharing their pronouns at every time. And so this practice is something that we provide as an invitation and visibility but it should never be a requirement.

Ann: Yeah, I was actually curious about that in terms of overall being aware of the language we're using and aware of, you know, sort of the gender implications of the language we're using, what are your feelings of defaulting to they? Or is there a proper thing to default to if you are not sure and you don't want to ask or make someone declare their pronouns to you? What are best practices when you're maybe just not quite sure about the parameters of what someone identifies as or would like to use?

Becca: Yeah, if you're not sure the default is really to not use pronouns for that person. So just use their name and try whenever possible to just use your language that's not using a pronoun for them. The best practice is to share your pronouns if you're comfortable with them when you are introducing yourself to someone and that's an invitation for them to share if they do have pronouns.

Ann: And that would be sort of how you introduced yourself to me at the top of the podcast saying "I'm so-and-so and I use these pronouns?"

Becca: Absolutely.

Ann: Yeah. Do you have best practices or suggestions that you give to people for when they unintentionally screw this up? Like your brain just grabs for the wrong pronoun. Because I think a lot of people listening to this are going to be like 100% I want to do my very best and also recognizing that we've all been conditioned with certain assumptions about pronouns and that we are probably not all going to be great all the time.

Becca: Absolutely. And that is why we do recommend practice because we know that this isn't just something that happens naturally and introducing yourself with your pronouns is something that is a practice that you have to kind of get into and that will feel more comfortable the more that you do it. And we do have a section in our pronoun guide that talks about like I mentioned misgendering and we know that that happens and we know that that isn't something that for the most part people are doing intentionally in order to hurt somebody. We know that just it happens.

(18:08)

So we do ask in that instance if you use the wrong pronoun for someone the best practice is to correct yourself, use the right pronoun, and then move on. I think one of the things that can happen -- you know, like you said people have really good intentions and they feel terrible when they misgender someone and it's something that we know that we see. But sometimes we can get into a space where we are apologizing so profusely it actually brings the attention back on ourselves and then it also asks some labor of the person who's just been misgendered to care for us or to notice us and to affirm that it's okay that we were trying. And so we just try to avoid that by not laboring in that moment.

Ann: So a good example would be if I say he when I meant they, just saying "Oh, excuse me, they" and then keep going.

Becca: Yes.

Ann: And not be like "Oh, I'm so, so sorry. I just -- oh my god, I just misgendered you."

Becca: Yes, yes.

Ann: You know what I mean? Sort of correct and move on.

Becca: Absolutely.

Ann: Yeah, that's extremely helpful. I'm wondering about -- if you could talk a little bit about the things that you're working on right now with regard to pronouns that you're really excited about, like maybe something new or something that you've got coming up that you might want to tell us about.

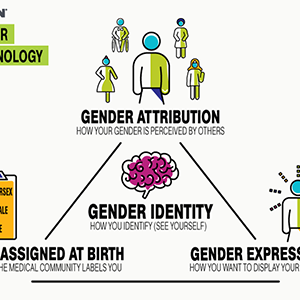

Becca: Yeah, absolutely. Something around gender that pronouns is kind of looped into that we're working on is an update on a visual that we have. It's called the gender triangle and it looks at gender identity, gender expression, gender attribution which is the way that our gender is interpreted by other people and kind of assumed by other people and then also bodies. And so it looks at these different aspects of gender and how they're related and how they can help us to better understand ourselves and others.

Ann: I love that. And so it's actually like a visual you can look at.

(19:50)

Becca: Mm-hmm. And it has -- actually we've partnered with Interact which is an intersex advocacy non-profit to create kind of this update of this visual and it will also have a discussion guide that kind of talks through the different aspects of gender.

Ann: Which is a great lead-in to if someone's listening to this and wants to maybe get some examples of how to write a bio or redo their email signature in ways that account for pronouns where can they go?

Becca: All of GLSEN's resources around gender and identity and trans and gender non-confirming student support can be found at glsen.org/trans and that's GLSEN is G-L-S-E-N. So at that landing page we have blogs by trans-identified students, trans-identified educators. We have the gender visuals I was mentioning. We have the pronoun resource guide and lots of different resources for this work.

Ann: Amazing. Becca thank you so much for being on the podcast today.

Becca: Thank you for having me.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: Ugh, so informative. Thank you.

Ann: I know. Turns out if it's easy enough for kids adults like me can also grasp what she's talking about. [Laughs]

[Ads]

(24:00)

Aminatou: This week I talked to Dr. Kirby Conrod of the University of Washington Department of Linguistics. We love a linguistics department and we love a linguistics PhD in this family so I was really excited about this one. And what we really got into was the history of gender pronouns and what's really different in this moment in history than other times about the way that we're talking about neutral pronouns. We really dig into the claim that singular they isn't grammatically correct or any kind of excuse that people have not to be precise with their language. You know, and I was just really excited to talk to somebody who was also like a words expert about how words can change and how much meaning they have.

[Interview Starts]

Dr. Conrod: I am Dr. Kirby Conrod and I am a recent graduate of the University of Washington Linguistics Department so I describe myself as a linguist. And what I'm interested about in linguistics is I'm really interested in the underlying structure of language and also how the sort of consistent structures that we find in language over and over are useful to us as social creatures.

So the way that this manifests in my dissertation is that I'm really interested in pronouns. A pronoun gives you social information about a person and that is context-dependent. So you will find that if you start really listening to what's going on around you you'll notice that people are switching pronouns about the same person in the middle of a conversation and they're doing this because they're telling you something socially. And so I am really interested in collecting that data and also comparing it to what we know about the structure of language and how we can make a theory that explains that readily.

(25:54)

Aminatou: I love that. Was that something that you were -- when you were drawn into this area of study was there a very obvious like oh, there's a program for that? Or there's already a body of work that can be added into. Or was it really just trying to find a space where you'd be able to intellectually explore these ideas?

Dr. Conrod: It puts me in a little bit of a weird situation coming into it is that I was a linguist before I was trans and so I came out as non-binary the same year that I started grad school but I was already fairly far into investigating syntax and the structure of language before that. And it wasn't until a year or two into my grad program that I started noticing our textbooks keep saying this stuff about pronouns that is just factually wrong.

Aminatou: Like what stuff?

Dr. Conrod: So intro semantics or syntax textbooks will sometimes tell you "Okay, here is an example of an ill-formed sentence." This is a sentence that the language shouldn't be able to generate is "Mary likes himself." And that's obviously social information that we're talking about here where you have to know socially something about the name Mary.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: And in fact if you are in sort of a social position where you happen to know somebody named Mary who uses he/him pronouns who wants to be called he then the language obviously does need to be able to generate that sentence. So it's really ridiculous to see introductory textbooks saying "Oh, this is just totally impossible, structurally never happens," and know from my perspective as a trans person with a lot of trans friends that's just not true.

Aminatou: Right.

(27:45)

Dr. Conrod: And so one of my big goals was I know this stuff is happening. I kind of just need to catch it on tape. I kind of just need to recreate it in lab conditions or find somebody doing this in the wild that I can say "Look, I wrote this example down word-for-word. It's verbatim," where somebody switched pronouns in the middle of a conversation and obviously they did it without having a grammaticality problem. They did it without even really noticing that they did it.

So it's something where if we're going to have a theory of language that says what is structurally possible we need to rule that in and not out. And that's sort of how I came about it was, you know, already being steeped in the study of linguistics but noticing that the received knowledge didn't really have room for trans and non-binary people already.

Aminatou: Wow, that's so fascinating. Can you give me an example of when you said that people just naturally switch out pronouns in the language they're using and they do that seamlessly, can you give me a sentence example of that?

Dr. Conrod: Yeah, one example -- and it's always going to be more than one sentence because it sort of needs a rich context to support it. But say that you're talking about your friend Laurel and you're talking to your friend Taylor. So you and Taylor are having lunch and both of you know Laurel but maybe Taylor doesn't know Laurel that well. And so you're telling Taylor "Oh yeah, Laurel just told me that they're moving to San Francisco." So you used they there.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: And you may be talking later and later it comes up "Oh yeah, Laurel doesn't really like her boyfriend." And so you can switch to she and there's not a conflict there, and that's for a couple reasons. One is that you are sort of giving social context for what information you're telling and you're not giving more information than is necessary.

(29:48)

So in the first instance maybe you used they because you know okay, Taylor doesn't know Laurel that well and so I kind of want to keep things simple and it's sort of not relevant what gender Laurel is in order to talk about a job that they took. And so people will just naturally do this where they'll use singular they not because the person they're talking about is non-binary or trans or anything but just because the gender's not really important.

And if you find later in the conversation when you do want to give a little bit of information where the gender tells you something, talking about somebody and saying her boyfriend rather than their boyfriend gives you a little bit more sort of social context for what kind of relationship this is. So maybe nowadays relevant.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: So this kind of example of it's not necessarily the case that the name is going to give you all the gender information and it's not the case that the person you're talking to already knows necessarily -- they may or may not know -- but you sort of turn the faucet on and off of how much information you want to give about the person that you're talking about. And so one thing that's really nice about singular they just as part of the language, and it's been part of the language for quite a while, is it lets us turn that faucet on or off in terms of how much gender information we give.

And then I have another example which is fairly different but still about the kind of social information. So have you ever watched RuPaul's Drag Race?

Aminatou: Of course.

Dr. Conrod: So have you noticed that when the judges are talking about a contestant and they're talking about a contestant that's doing very well they always use she.

Aminatou: Yes.

Dr. Conrod: And most of the contestants use she for each other most of the time and the times when they don't, when a contestant is starting to do poorly, the judges will start using he.

Aminatou: Wow.

Dr. Conrod: And they won't do it 100% of the time. They won't do it 100% of the time but they will do it specifically when they're talking about the failures of the gendered performance. And it's not that necessarily oh, you did drag so bad that you became a man because your gender situation sort of relative to your identity is the same. It's just that we're not giving you this extra fancy pronoun that you usually get when you dress up.

(32:13)

Aminatou: You're blowing my mind right now. I don't think I had ever noticed that. Or rather it just felt so seamless, you know, in the conversation and I never processed it that way.

Dr. Conrod: So this is one of the things that makes it really hard to talk to people about pronouns and especially about the way that people use pronouns themselves is that you are not noticing kind of by design pronouns are what we call a grammatical category or a functional category where they're part of the building blocks of the language. They really are structural rather than contentful. And so most people don't notice what pronouns they are using when they're using them. You have to really draw their attention of really, really like play back a recording of what you said and they'll be like oh my god, I had no idea I used this pronoun.

And that makes it very difficult for example when a trans person is trying to correct somebody who's misgendering them a lot, people will have no idea. They will genuinely not know oh, I used the wrong pronoun because your brain sort of is doing that under the hood. It's not part of what you think you're putting together when you're putting together a sentence.

Aminatou: Wow, I'm still processing the drag race example. That is fascinating. [Laughs]

Dr. Conrod: I love the drag race example.

Aminatou: Listen, if this is your party trick it works because it's working on me. [Laughs]

Dr. Conrod: Yeah, it's my party trick because it's so, so clear of like there is obviously no change about the person that we're talking about and it's also nothing to do with grammaticality because there's no singular they involved. That's one of those things of like it's a good party trick because it doesn't invoke the grammarian sort of singular they fighting spirit. It's just like no, he and she are definitely pronouns. You agree they are grammatical and normal so switching between them, you know, sort of air quotes "it shouldn't be possible." But we're doing it and we don't even notice that we're doing it.

(34:15)

Aminatou: I am curious about what you think is different in this moment in history than other times when people have proposed gender-neutral pronouns. You know, I can't quite decide if I feel that it's a moment and something is happening and the world is a tiny bit open to it or if it's just the function of the people that I hang out with and the environments that I'm in where more and more it's something that people are thinking about.

Dr. Conrod: I have two answers to this and one of them is a nerdy answer and one of them is a cool social answer.

Aminatou: Please tell me both. [Laughs]

Dr. Conrod: Okay, which one do you want first?

Aminatou: Um, I'll take nerdy for 100 Dr. Conrod.

Dr. Conrod: Yeah, so the nerdy answer is that the grammatical change that allows people to use singular they with a proper name talking about a specific person has been going on for a couple decades now and it's just about hitting saturation and that's why it suddenly seems like a huge topic is that the people for whom it's completely natural and grammatical are hitting college age.

And so as a PhD student when I'm a college instructor I'm teaching my, you know, syntax class. Every time I start a class I do a poll on the first day of class, on syllabus day, partly to just sort of gauge where my students are at with singular they and see if they're going to be rude to me or not. Then partly because I like having a way to sort of calibrate them for what they're going to be looking for when they're looking at language.

And what I found is that for the past three or four years 100% of them are completely fine with singular they. No grammatical problems. So the 19- to 22-year-olds are just -- they're at saturation. They have hit the ceiling of they're all fine with it. And the reason that this is sort of a big deal is we're hitting a certain point in the millennial generation aging into we're actually adults now. I'm sort of a mid-millennial, and so I just turned 30 this year and I'm in this weird position of interfacing with college students a lot.

Aminatou: Yeah.

(36:25)

Dr. Conrod: Who are definitely Gen Z and I'm interfacing with baby boomers a lot who are mostly the people I'm doing job applications with. What I'm finding is that the grammatical change that I've measured in my data of just sort of asking people to rate sentences -- and I had people write a whole bunch of sentences with different kinds of uses. But just looking at using singular they with a proper name, what you'll find is that after about the birth year of 1985 everybody's totally fine with it which includes older millennials. And before about 1985, so Gen X, is sort of variable where people will go one way or the other. And then before about 1976 or so is where you get sort of the baby boomer cutoff of like they really don't like it.

And so you get this really clear sort of generational effect and the reason that it's such a big moment right now is because it's not just something that the kids are doing; it's these people like me who are entering the real grownup workforce and have a real whole PhD and are just like yeah, it's just already part of the language and you don't really get to kick up a fuss about it. It's weird that you're kicking up a fuss about it. And so I think that's kind of where the big attention is coming from just in terms of like noticing the language change that's been going on.

Aminatou: Yeah. You said that you would give me a nerdy answer and a social answer.

Dr. Conrod: Oh yeah.

Aminatou: So I'm waiting for the social answer now.

(38:00)

Dr. Conrod: The social answer is that I don't think that the structure of language shapes or constraints thought completely but it does make it easier to voice certain thoughts. And I do know that just me as a non-binary person, I had a lot of an easier time figuring out that identity once I had the words to put to it. And I think that at a certain point you reach a tipping point where the words are popular enough and they're widely enough discussed that people are realizing that you can just be non-binary if you want to.

And this is something that I'm extremely evangelical about of like I would -- I would love for more people to really dig in and say "Am I really attached to being a woman? Does it bring me strength and identity and does it make me feel whole and joyful when people see me as a woman?" And for me the answer was no and I don't feel that way about manhood either. And in fact the idea that people could use gender as a sort of shortcut to trying to understand me is sort of insulting to me.

And that was one of the feelings that drove me towards oh, well I'm going to just stop doing that then. And like realizing that you can stop doing that -- like in some way you need to see somebody doing that. You need to see an example of this is a possible thing. You know, people are out here sort of synthesizing the idea on their own but it's difficult and it's rare and it's a lot easier once you see, you know, a certain amount of media representation but also just the discussion of singular they that's been happening sort of in popular culture has been introducing the idea of non-binary identity to people that wouldn't have thought of it otherwise.

(39:50)

And I think that there's a certain point where that sort of snowballs and the social moment that we're having is the snowball getting big enough that it's rolling down the hill and nobody can stop it. Of, you know, gender is optional now.

Aminatou: Ugh, thank goodness. We're getting there.

Dr. Conrod: Yeah.

[Ads]

(42:10)

Aminatou: One of the things that really drives me up the wall is hearing people that claim that singular they, it's not grammatical or every kind of . . . that's kind of a 101 excuse for not taking an inclusive approach to pronouns. And so I'm just interested in how you respond to those people.

Dr. Conrod: I have a couple of different responses to those people depending on who they are. So when I'm talking to somebody who's not a linguist they're using the word grammatical to sort of mean what I learned in grammar school or what I learned in grammar class and it's almost always an excuse to cover up a social issue that they have. And they really don't like when I suggest "Well why don't you just avoid pronouns about me then? If you really don't like using singular they don't use a pronoun at all. I'm not giving you any other options." And people really don't like that. [Laughs] Where certainly, you know, if grammaticality were actually the issue here then avoiding pronouns would be the only respectful sort of recourse that they could take.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: Of like okay, if my brain seriously won't let me produce this then I have to figure out another way to talk about this person that doesn't involve misgendering them and they just refuse to do that work of, you know, slow down when you talk and think about how you're talking and if you don't like singular they then don't use any pronouns. So that's one issue.

And then the other issue is that the word grammatical means different things to different people. When a linguist says grammatical what we are referring to -- and this is an issue because I will get into fights with older linguists about it -- what they're referring to is does the sort of internal structure of language as it exists in the brain produce this naturally?

(44:05)

And so when a linguist says singular they is ungrammatical what they mean is I haven't sort of been able to partake in this language change that's going on. So it's not that I think there's a rule against it necessarily; it's that when I say it my brain resists it.

Now interestingly these people also have been really resistant to the advice of just avoid pronouns then and I'm kind of . . . I'm kind of curious why that is. It's been sort of an issue of there's a changing of the guard going on in linguistics the same way that there is going on everywhere else right now of if you find there is actually legitimately a grammar issue sort of embedded in your brain that doesn't let you refer to someone the way they want to be referred to that's not just a question of grammar; that's also a question of, you know, etiquette and professional respect. And what you're going to do about it tells us a lot about you as a person, you know?

Aminatou: I think that also for people who are linguists it's . . . to me that just seems like such a lazy cop-out because the brain adapts to learning all sorts of information but also you have people who are fluent in languages that have completely different grammatical structures. I'm like it's possible.

Dr. Conrod: Yes.

Aminatou: It is completely possible for your brain to process that information or to learn a new way to organize that thought pattern. And so just hearing you talk about this resistance in so many ways, I think that again it just says so much about the people who are resistant -- you know, who are resistant to the change -- than the people who deserve to have their pronouns acknowledged.

(45:48)

Dr. Conrod: It's a lot like learning a second language in a way that, you know, if we're linguists we should not be super obnoxious about someone asking us "Can you learn a second language at least a little bit in order to not be rude?" It's hard because it's not just using a new word. It's a functional part of the language.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: It's a structural part of the language. And so when you're learning to use it as an adult it's not as easy as just learning to use a new noun that you heard. It's not like picking up a new slang word. But that said it doesn't mean that it's impossible. You would just have to practice it more like you practice a second language where you have to give yourself opportunities for rehearsals.

I heard a really cute story online. Somebody's parents were having a hard time practicing singular they and what they decided to do, the parents decided okay, now our cat is non-binary and our cat uses singular they.

Aminatou: Yes!

Dr. Conrod: And this gives us an opportunity -- it gives us an opportunity to practice and if we mess up it doesn't hurt the cat's feelings which is really nice because it's really hard to practice on real human beings because if you mess up you do hurt the human being's feelings.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Dr. Conrod: But one miracle of cats is that they don't care what pronoun you use about them and that's very valid of them.

Aminatou: I love that example. We're obviously doing this podcast in English so that's our focus but I was wondering if there are other languages that are easier to adapt to a variety of gender identities. I'm a French speaker and one of the things that really has been really hard for me is all of the conversation that I have around language and gender identity in a positive way is in English and French is so -- everything is gendered. Every object is assigned some sort of useless gender function. And really trying to think about how to untangle that knot. But I'm just wondering if there are other languages that make that easier or have been offering solutions.

(47:54)

Dr. Conrod: The first thing I will say is that there's some very new and very exciting research coming out in linguistics right now mostly from very young linguists, early career and grad students. And we just had a conference about it and so we all got together and talked about it. But the French situation which is kind of analogous to the Spanish situation is that oh, well all the nouns have gender. And there's this confusing issue of we use the word gender to refer to two different things.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: So grammatical gender we're moving towards calling that noun classes because it doesn't really have an inherent connection with the way we use the word gender about human beings.

Aminatou: Right.

Dr. Conrod: So a table is not really inherently feminine or masculine. A table is a table and if you're attributing person-like qualities to it based on oh, it has the same sort of phonological ending of it ends in oh or ah, that's on you. It's not about the table. And the fact that tables are different genders in different languages means that it's obviously nothing to do with the table itself.

So we're calling that sort of gender of all the things, we're rebranding that and we're calling it noun classes now. And one of the reasons that we want to do that is so we can separate out talking about noun classes from talking about the gender -- the social gender -- of actual human beings.

One thing in French that I know is that there's some sort of dots situation where you put dots in-between all the endings so that you just put all the endings on. This only works in writing. I don't know of a spoken solution in French right now but I do know people are looking into it.

In Spanish Spanish has a slightly more I think regular gender system or like ending system than French. And so what some people are doing is that instead of the o or the a endings they're just replacing everything with e, like spelled with an orthographic E, and this sort of makes like a new flattened gender. And the reason that this is possible -- and some people find it quite difficult to do for the same reason of it's structural and it's part of the building blocks of language -- but some people will find that because it's like some nouns that already exist you can just sort of extend the pattern of well there are already nouns that end in e so we're just going to decide that all nouns end in e now. Doing this specifically for nouns that refer to people rather than nouns that refer to tables because again the tables do not care.

(50:33)

You know, what I'm interested in as a linguist is sort of watching and waiting to see what the trans and non-binary people who are native speakers of that language just end up doing. There's, you know, situations in other languages where Chinese doesn't have any gender pronouns at all and so it's not necessarily the case that speakers of Mandarin think everybody is non-binary. That's definitely not true. But the pronoun for he and she are spoken exactly the same. You get the sort of effect of people will use more like nouns and stuff to talk about gender when they want to talk about it but it's not like structurally embedded in the language.

Aminatou: Got it.

Dr. Conrod: Language users are doing something within an infinitely generative tool meaning that the constraints are coming from creativity, not from the language itself. So if it is the case that there area bunch of trans and non-binary Spanish speakers who want to figure out what to do they will figure it out. If it means that Spanish changes that's like a natural consequence of social forces driving language change and this happens all the time. You know, it's the reason that nobody's speaking Latin anymore is that the language changed to fit its setting and this is a natural process that's going to happen whether people are mad online about it or not.

Aminatou: Latin canceled. [Laughs]

(52:00)

Dr. Conrod: Yeah.

Aminatou: That's so real. I guess this is probably the first question I should've asked you but maybe this is a good place to end is why is it so important to be precise with our language? What is at stake here?

Dr. Conrod: A couple things. One of the things that is at stake here is just basic respect. It's easier for me to couch this in terms of etiquette. When I ask somebody to use a certain set of pronouns about me my request is almost nothing to do with the language itself and more to do with please show me that my identity and my idea of myself matters to you.

Aminatou: Hmm.

Dr. Conrod: And it's a lot the same way of calling somebody the name that they want to be called. It's just that it's a smaller part of the language. But what's at stake is really the divide that we're seeing of people who are really, really resistant to changing their pronoun use are also people who really just fundamentally don't want to be told what to do even if it comes at the expense of hurting the people around them. And I think that that tells us more about them than their grammar.

Aminatou: That's so true. Thank you so much for joining us today. You are . . .

Dr. Conrod: Thank you.

Aminatou: An iconic linguistics PhD. I'm so into it.

Dr. Conrod: Thank you so much. I'm really excited to be brought into this conversation so thank you so much for thinking of me and reaching out. I'm really flattered honestly.

Aminatou: Of course. And where can we find more of your work for the listeners at home?

Dr. Conrod: So my website is kirbyconrod.com and I need to put more PDFs on it. And my Twitter is probably the best place to find me and my handle is just @kirbyconrod and that's C-O-N-R-O-D. A lot of people misspell that. And my Twitter is sort of going through a transitional phase right now because I am sort of graduated but it's where I talk about my thoughts about language and linguistics as well as sort of my experiences in grad school and in the academy. So it's also the place that I check the most.

Aminatou: Great. Have a wonderful evening and thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Conrod: Thank you so much.

[Interview Ends]

(54:25)

Ann: Linguistics forever, we love all of this. So what pronouns do you use Aminatou Sow?

Aminatou: I am she/her and to quote Alicia Garza a diva. [Laughs] Those are my pronouns, she/her/diva.

Dr. Conrod: [Laughs] I am also a she/her and that is now in my email signature like a champ.

Aminatou: I know! Thank you for making me make that. Like not as peer pressure but thank you for inspiring me to do that as well.

Dr. Conrod: I mean it is really -- it's the kind of thing that it took, as I said to Becca, it took someone in my life being like "Um, hello? Why is this not in your email signature?" And I was like you're right. Sometimes this is like the group accountability, like the language we all use with each other. The person who sees your email signature multiple times a week, it takes that person being like "Hey, you can do better."

Aminatou: Right. And it really -- it costs you nothing to do better so let's all do better.

Ann: All right. See you on the Internet.

Aminatou: See you on the Internet boo-boo. Congrats on your book. Can't wait to read it.

Ann: She/her/you on the Internet. [Laughter]

Aminatou: You can find us many places on the Internet: callyourgirlfriend.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, we're on all your favorite platforms. Subscribe, rate, review, you know the drill. You can call us back. You can leave a voicemail at 714-681-2943. That's 714-681-CYGF. You can email us at callyrgf@gmail.com. Our theme song is by Robyn, original music composed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs. Our logos are by Kenesha Sneed. We're on Instagram and Twitter at @callyrgf where Sophie Carter-Kahn does all of our social. Our associate producer is Jordan Baley and this podcast is produced by Gina Delvac.